Aaron Read

Published Issue: Summer 2008

His dad, Christopher Ford, was a television commercial producer in live TV. It was a great job, even if his two sons didn’t always realize it at the time. He did all the live cheese pours for “Kraft Musical Hall,” which eventually became “The Perry Como Show.” He would fly every weekend to New York and melt a big tub of cheese and pour it on camera for a mesmerized television audience. It was the 1950s and cheap American cheese was what you were supposed to melt and pour over everything that was possibly edible.

His dad, Christopher Ford, was a television commercial producer in live TV. It was a great job, even if his two sons didn’t always realize it at the time. He did all the live cheese pours for “Kraft Musical Hall,” which eventually became “The Perry Como Show.” He would fly every weekend to New York and melt a big tub of cheese and pour it on camera for a mesmerized television audience. It was the 1950s and cheap American cheese was what you were supposed to melt and pour over everything that was possibly edible.

Christopher Ford also did live commercials for ALL Detergent. He created a Plexiglas washing machine to photograph the detergent cleaning the clothes.

There were other shows, one was “Sky King,” another one was “Watch Mr. Wizard” and a third one was “Zoo Parade” with Marlin Perkins. Christopher Ford was curious enough to find people he thought were interesting and build a show around them. Marlin Perkins was the first zoologist on television and later found real fame with his long-running mainstay “Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom.”

Every Saturday Christopher Ford took his two sons, Harrison and Terence, to the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago to film Marlin Perkins pulling animals out of their cages.

Everything was live. There was the intensity of playing with fire. If the snake bit you on camera, the snake bit you on camera.

Ford did one show called “Super Circus.” A client went to him, in this case it was Skippy Peanut Butter, and asked him to create a show for kids.

He figured out that circuses traveled on trains. They all had to go through Chicago. They’d stop for a day or two to feed the animals, rest or do a show and then travel on to Kansas City or wherever else they were going. Ford got a bunch of the circus performers to do a show at a theater in downtown Chicago, and he hired a ringmaster. The young man wore a black hat and a red-tailed coat and white riding pants and big, tall riding boots. It was his first job on camera. He became a little more famous as the senior correspondent for “Sixty Minutes.” It was Mike Wallace.

The Fords weren’t getting rich but they were doing well. Terence said, “It wasn’t bad for a guy who never finished grade school and was sleeping on a park bench at one point during the Depression.”

They ended up owning two or three homes. When Terence, the younger of the two boys got out of high school, Christopher Ford became a successful voiceover actor.

He lived to be 92.

He was a tough guy. Typical of the time, there was not a lot of hugging and kissing and not a lot of dad activities with his kids. He just didn’t know how; he didn’t have a dad. His wife, Dorothy, was married to him for 60 years. She brought some soft edges to the curmudgeonly orphan Irishman from Hell’s Kitchen.

Dorothy was the affectionate one. They laugh that she was a great mother, but a terrible cook-everything came out of a can then. The boys still talk about the meals she fed them.

Terence got a job at a bookstore when he was 16, and then worked as a caddy and a bus boy. Harrison had a job as a cook on a yacht in Lake Michigan. Everybody worked because that was what we were taught, that’s what your value was; you worked and you worked hard.

It was also expected that they would go to college.

Harrison went to Ripon College. He wanted to be an actor. Along the way he figured out how to be a carpenter. He married young, a father when he was still in his early twenties, two boys, and when he moved to Los Angeles he got there at a time still affordable to working families.

His brother commented to California Conversations that it wasn’t always easy.

“There was a long time where my brother was as poor as you could imagine and he had a young family to support. That’s all public history; working 14 years as a carpenter and only sometimes working as an actor.”

“I remember when I first went to California in 1968, he had no money, was working hand to mouth as a carpenter, not getting any acting jobs, and people would come and say your brother’s going to be a big star one day. He had a small house on Woodrow Wilson Drive near Universal Studios. Of course my response was, ‘Yeah, right, do you see how the man lives?’”

“Here’s the story. He called me up and said can you take me to the airport. I’ve got a job in London. I thought that’s great.”

“I picked him up, and he came out with a gym bag. I said tell me about the job, and he said it’s a lead in a science fiction movie and they’re going to pay me $10,000 to do it. I got the money up front so the kids have something to eat while I’m gone, and by the way that’s my sports coat you’re wearing...and do you have any money? I gave him $20. When I pulled up to the airport I asked about the movie.”

“He said I play an adventurous space pilot who flies through the universe with a 9-foot tall monkey at my side. I said oh, no, first lead and you get this? And he said, well its $10,000 and its more money than I’ve ever made.”

“He got out of the car and went to get on the plane. I got back in my car and started the engine. The muffler fell off.”

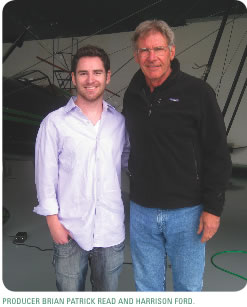

We met with Harrison Ford at his private airport hangar in Santa Monica. There was a low sky and he was not able to fly like he wanted to. The vast space was spotlessly clean and on a small table someone put out juice and muffins. There were several planes belonging to the actor parked in view. There was also a helicopter Ford likes to fly.

There is a description of Indiana Jones in a novel authorized by his creator, George Lucas: The man who led the group was called Indiana Jones. He was muscular in the way one might associate with an athlete not quite beyond his prime. He had several days’ growth of dirty blonde beard and streaks of dark sweat on a face that might once have been handsome in a facile, photogenic fashion.

It was not an accurate view of Harrison Ford when he first played the part in 1980. It comes much closer to him now.

In the past, both George Lucas and Steven Spielberg have described Ford as not being a traditionally handsome leading man-calling him naturalistic or a star in the tradition of a Humphrey Bogart.

Hollywood obviously has a higher standard than the rest of the world when it comes to looks because at almost sixty-six, Harrison Ford not only appears much younger, much healthier, much stronger and much sharper than others within his loosely drawn baby-boomer demographic, he is someone who would get your attention if he’d never become famous. He has the face with which he was born. There has not been any work done by clever doctors. His eyes are clear. His voice and demeanor are not much different than what you pay to see in the theater. He is polite, without being effusive. He is busy, yet doesn’t make you feel rushed when he sits down to chat. There has been a great deal written about his decision to wear an earring-he has a black stud in his left ear. It lends some rakishness.

He is a tad bit less than six feet-and I don’t mean that sports program or action hero bio fiction that places imaginary lifts in the descriptions of those we only see on screen. He translates in life very much like he does in his movies.

California Conversations: Your brother has been taking your picture for us all morning.

Harrison Ford: He’s been on the job.

CC: What is it about a brother that is so special?

HF: You don’t have any choice. You’re stuck with each other from the beginning. I think that’s part of what’s special about them. You either make peace with your brother or not. I enjoy my brother’s company. We’re different, very different choices, different lives. He lives up in Northern California so we don’t see that much of each other, but we were quite close at certain points in our growing up.

CC: Were you guys known as the Ford boys in the neighborhood?

HF: I suppose we were. I don’t really remember being known as the Ford boys, but I suppose we must have been.

CC: Boy Scouts was important to the Ford family.

HF: Well, yeah, I never got any further than star scout myself, but I did work in a Boy Scout camp as an assistant counselor or a counselor, I don’t remember now, back in Wisconsin. I really enjoyed it. I’m really pleased that my brother’s son has taken scouting seriously. I think he’s within one merit badge of being an Eagle Scout.

CC: Scouting is not as big as it used to be.

HF: No, I don’t think so.

CC: Were you more a product of the ‘50s or the ‘60s?

HF: I think I was a product of the ‘50s until the ‘60s came along, and then everything changed. I may have been in the front end of it, but I was certainly a part of the cultural revolution of the ‘60s.

Ford made his first movie in 1966. He was twenty-four years old. It would be more than a decade before he could actually live the life of an actor. He has obviously managed to silence those who thought he didn’t have the skills to make it big on the screen, and he has certainly done more than he expected. His films have grossed more than 600 billion dollars worldwide.

CC: It seems like there are certain stars with extraordinary careers, and yet they manage to be scandal-free, and have a private life that is essentially very private.

HF: Well, my theory is that people only have a certain amount of interest in any one person and it’s best to save that interest until you have something worthwhile to bring to their attention. In the baldest possible way, you could say, until you have something to sell. I’ve never had a publicist. I try to stay out of the public view, until I have a movie. Then my rarity has some value at that point.

CC: How do you keep the protective wall and still deal with fans asking for an autograph?

HF: Well, they’re more than fans. In my case, I tend to think of them as customers. Being an actor is like living above the store. You’re always open for business. If your eyes are open, your store is open. Folks often want to engage you, and I don’t really mind. Once you make peace with the reality of fame, you do what you can to service your customers within reasonable limits.

CC: Did you dream of fame when you got into the movie business?

HF: No, no I never did. All I dreamed of was making a living as an actor and not having to do another job. It frankly never occurred to me that I had the opportunity to be famous in the business or be as successful as I was lucky enough to become. I always thought if I got a regular job on a TV series that was sort of the height of my ambition.

CC: 1973 you make American Graffiti...did George Lucas take you to Modesto before or during the filming to see the hometown that inspired him?

HF: No. I had seen Modesto. I had been through Modesto, but I don’t remember if it was before American Graffiti or after. The character I played in American Graffiti was based on...I’ll tell you how it came to be. George Lucas wanted me to get a crew cut so that I looked different than the other kids in American Graffiti. He wanted some distinguishing character element. As it was the late ‘60s...was it 1962? It can’t be 1962, I was still in college.

CC: The story was about where were you in ‘62?

HF: Right. Well, in 1962 I was still in Ripon College...so, in 1973 or so when I made the movie, I didn’t really want to get a crew cut. I thought it was a disadvantage for me if I wanted to get other roles. American Graffiti was a short part, and I had longer hair at the time. In any case, I suggested to George that instead of the short hair that I wear a white cowboy hat. It reminded me of those kids in high school that kind of got stuck on Western Days and find a character for themselves in that context. I thought that it was appropriate. George went along with the white cowboy hat.

CC: When did you realize you had a chance for real stardom?

HF: American Graffiti was successful, and it did bring some opportunities, none of them really significant. Part of the problem or at least part of the deal was that between American Graffiti and Star Wars I was determined to only take better parts in better pictures with an increase in pay. I was still a carpenter at the time. I almost didn’t take the American Graffiti part because the pay was so low.

CC: I think I read you got $500.

HF: Well, that’s what I finally got. They offered me $485, I think.

CC: You negotiated the extra $15?

HF: I did.

CC: Good for you.

HF: (laughs) It made a difference.

CC: You’ve told the story in the past about being in a movie called, Dead Heat on a Merry-go-Round.

HF: Right. I was in the movie. I don’t know if I’ve told many stories about it.

CC: You played a bellhop.

HF: Right.

CC: And someone in the industry said to you that…

HF: Right, yeah, it was the head of the new talent program at Columbia Pictures, a guy who was in charge of managing the careers of four or five guys and about seven or eight girls that were all under contract with Columbia Pictures. He called me into his office the day after I played a bellboy, and told me the story of Tony Curtis who...as he related it to me...delivered a bag of groceries in a movie, and this guy took one look at him and knew Curtis was a movie star. I was a smart ass kid, and I leaned across the desk and said, “I thought you were supposed to think it was a grocery delivery boy.” And that ended our relationship pretty much right there. He threw me out of his office, and a year and a half later he recommended that Columbia drop my contract, which was great with me because I was not happy about the kind of work I was doing. I was getting $150 a week and all the respect that implied. There was a point where I learned a theory of intrinsic value-you’re worth what they pay you.

CC: How many of those other individuals who were with you in that program went on to become successful actors?

HF: A few of them had some measure of success at various times. I don’t think anybody is still in the business that was in the program I went through.

CC: Star Wars changed everything?

HF: It did. I was able to make the kind of choices that mattered to me as an actor.

CC: Big parts and small-small part in Apocalypse Now-you were able to choose a name for your character?

HF: Yeah, I just...Lucas, I guess it was for George Lucas. I did choose a name for the character because the character was nameless, one of two nameless parts I played for Francis Coppola.

CC: The Academy Award nominated, The Conversation, being the other?

HF: The Conversation being the other character who got a name at a certain point, but I don’t remember what it was. When I went to pick up the script for it, it was called “young man.”

CC: That was a great movie, too.

HF: That was an interesting movie. I made it just after American Graffiti. It was important for me at this point to be making these kinds of films.

CC: George Lucas...how close is the friendship?

HF: I think we are friends. We are business associates, you know. We don’t have a close personal relationship. I know his kids and he knows my kids.

CC: You’re not buddies.

HF: No, no, not really. Again, part of it has to do with proximity. George lives up there, and I live down here. We have different lives.

CC: We always read that Tom Selleck was the first choice for Indiana Jones.

HF: Well, that’s quite correct.

CC: That’s true?

HF: Yeah, in fact, he was signed to do the movie, but he had a prior contract, I believe it was with NBC, to do his television series...Magnum.

CC: Were you second choice?

HF: Oh, I might have been third. I have no idea.

CC: Did you have to audition for it?

HF: I didn’t have to actually audition. The first time I heard anything about it relating to me was when I got a call from George saying he was going to send me a script. I read the script for Raiders of the Lost Ark, and I called him up and told him it was great. He said why don’t you go over and meet Steven. I went over to Steven’s house and met him for the first time, and we talked about the script. I might have read for him. Steven knew me from Star Wars and other things, I imagine. We got along very well. The conversation went well, and I think I left with the part.

CC: Do you watch yourself on screen?

HF: I do it all the time.

CC: You’re comfortable with it?

HF: I have to be able to watch myself with a professional point of view. I have to be able to participate in the process when I feel it’s necessary. I watch dailies and if I don’t like something I have in the past asked to do it over...it helps me in the process of the creation of a character and, when the characters are pretty much set, then it’s a question of keeping an eye on what we’re doing.

CC: The first time you saw yourself on the big screen, did you see yourself differently and say, yeah I’ve got a shot at this?

HF: (laughs) No, I saw myself as a bellboy.

CC: (laughs)...some of your movies are such huge movies, spectacular movies…

HF: Some of them.

CC: Do you worry sometimes that the craft of what you’re doing gets lost in the spectacle?

HF: No.

CC: Not at all?

HF: No, I stay focused on the film and how the character relates to the film and what part of the story it’s my job to tell; what is my relationship to this event. I often work closely with the directors and producers. I have script approval. I understand what it is I’m doing. I think you’re probably referring to the old canard of the story being upstaged by special effects. I think that only happens in a really bad movie, when people have their elements out of proportion, out of control. So, I don’t worry about it.

CC: You’re about to have a movie released-Crossing Over with Sean Penn and Ray Liotta…

HF: It’s an ensemble piece.

CC: Controversial subject?

HF: Only if you feel strongly about immigration in any way.

CC: I just saw that after the economy, immigration is the number two issue on the minds of people in California.

HF: Well, I think the film is, or maybe the theme is, controversial, but in fact it is not an effort to be controversial. It is meant to be a balanced glimpse at four or five different stories that intertwine. I play an agent in immigration and customs, an ICE agent, an enforcement agent, which is now part of homeland security and I think the film is a fairly balanced look at a number of different immigrant communities.

CC: Do you get nervous before a film gets released?

HF: No, I don’t get nervous. I’m not nervous. I want the film to be as good as it can be, so I am very interested in how it is coming together.

Harrison Ford has five children. He is protective of their privacy, probably not an easy task for one of the most famous men in the world.

California Conversations brought two young reporters with us to the Santa Monica Airport when we met with Ford. They were eleven and eight-and-a-half. We asked Ford if he would mind taking the time to let them ask questions. There wasn’t any early warning. Ford doesn’t surround himself with publicists. He handled it as though they were just as important as the writers from the San Francisco Chronicle or the Los Angeles Times.

At one point he held the recorder to answer the questions. He liked them enough not to let them be overly-impressed with him.

CC: Do you have a star on Hollywood Boulevard?

HF: Yeah, I do actually. But there’s a funny story about it. There are two stars on Hollywood Boulevard with the name Harrison Ford on them. One of them is for an old silent screen actor who had the same name. You know, he was in movies before they had sound, and his name was Harrison Ford, too. His star is out in front of a famous restaurant, and mine is in front of the Kodak Theater.

CC: What is your favorite movie you have been in and why?

HF: I don’t really have a favorite movie. I have five kids...it’s sort of like asking which is my favorite kid, you know. There’s no answer to that. They’re all different. They are special for different reasons.

CC: If Indiana Jones and Han Solo met, would they be best friends?

HF: I don’t think so. Indiana Jones is a professor and an archeologist. Han Solo is a space pirate, so I don’t think they’d have very much in common. I don’t think they’d be friends.

CC: If you could be in any movie ever made, what would it be?

HF: If I could be in a movie, what would it be? Do you mean if I was to dream up my favorite idea of a movie that I haven’t been in yet, what would it be? I don’t know. That’s really hard because I always start when somebody sends me a script or when I get an idea for a script and then we see whether or not that turns out to be a good idea. So, I don’t know.

CC: Can you tell when a movie is going to be good?

HF: I wish I could.

CC: Who was your favorite co-star in a movie?

HF: I don’t really have a favorite co-star. Again, it’s very hard to say. Each person is different. Each movie is different.

CC: How do you choose what kind of movie you’ll do?

HF: I look for a combination of elements. I look for a good story. I look for a character that’s different from what I’ve lately done. I look for good directors to work with.

CC: You can choose any director now?

HF: No. It doesn’t always happen that way. I mean, I don’t choose a director unless I develop the script, which in some cases I do...or it comes to me without a director attached and I ask to participate in the choice of a director. But, many times a project will come with a director attached. Of course, I’m interested in who that director is and I’ll do my research if I’m not familiar with his work, and we’ll see what the personality mix is. I’ll meet somebody and talk to them about the movie.

CC: You’ve worked with so many great directors, do you ever stop and look at an actor like Clint Eastwood, who’s become, at 78, one of our most distinguished directors, and think you’ll get into directing yourself?

HF: I don’t know, maybe when I’m Clint’s age. Right now, I like the job I’ve got. That said, I don’t really want to direct because it takes too long, it’s too hard, and it doesn’t pay very well. Those are all still very good reasons not to do it.

Ford said it would be ‘terribly arrogant’ to say the newest ‘Indiana Jones’ would be a huge hit, although he did say with hinted humor that he expected it would make its money back. The reviews have been mostly good. Almost every writer has mentioned how he is still able to pull off the physically demanding role. The financial returns have been blockbuster numbers.

CC: Flying has become one of your favorite activities?

HF: Yeah, I think it has the importance of another life. I didn’t start flying until I was about 52 or 53. I didn’t know whether or not I’d actually be capable of learning something as complex as flying. I became intrigued by it. It has changed my life completely. It’s given me an alternative identity.

CC: What was your first flying experience?

HF: Well, I had a couple of lessons in a Piper Tripacer when I was in college, but I think it was about $11 an hour for the airplane rental and the instructor. I ran out of money fast and couldn’t afford it. So, years later when I determined that I was going to start flying again, I bought a Cessna 172. I kept that. I was working a lot at the time and taking my lessons. I was flying out of Jackson, Wyoming. I got my license in a Cessna 206.

CC: Today, you have quite a collection of planes.

HR: I do.

CC: Do you have any favorites?

HR: No. I think each plane is very different, suitable for different purposes and I enjoy flying them all.

CC: It looks like you run the gamut, from a bush airplane to the DeHaviland. I saw a tail dragger. Are you getting some seat of the pants flying experience?

HF: Yeah, I have three tail draggers, actually. Then there’s the DeHaviland Beaver and the Waco bi-plane, a 1929 Waco bi-plane.

CC: It’s an incredible plane...a lot of options.

HF: I enjoy backcountry flying. We have a trip that a bunch of us take. It started out with five or six, now it’s about fifteen airplanes. The guys get together and we spend four or five days up in the Frank Church wilderness in northern Idaho. We camp at one place, and then each day we set out to do a bunch of different little mountain strips.

CC: These are like dirt strips?

HF: Some of them are grass and nicely maintained, but most of them are kind of rough, dirt strips.

CC: I also read where you did some rescues.

HF: I had my helicopter in my backyard in Jackson, Wyoming and the Teton County Search and Rescue, which was operated under the authority of the Sheriff of Teton County, didn’t have a helicopter available on a regular basis for rescues. I volunteered my helicopter and my time as a pilot and I was lucky enough to be with 250 other people participating in a rescue. I mean the number of other people involved and the training they do fulltime in search and rescue is remarkable. They devote a lot of their life to this endeavor and then I come along and pick somebody up and they’re on Good Morning America the next day. Suddenly I’m the only, you know, the only hero in sight, which is, of course, complete rubbish. I’m lucky enough to stumble across somebody or be available to give somebody a ride to the hospital. That’s basically what it amounts to.

CC: It’s nice of you to state it that way.

HF: It’s been an honor. It’s a pleasure to be able to help people, and it’s also interesting to do the technical flying that’s sometimes involved, although I haven’t had the helicopter up in Wyoming for some period of time...this was mainly during the period when I was living there fulltime, and that’s not possible at the moment.

CC: You’re also active with the Experimental Aircraft Association.

HF: Yeah, I’m the chairman of the Young Eagles, which I think is a very important program, both to give kids a sense of something in their lives that they might really enjoy doing, either recreationally or as a vocation, and I think it’s also important that we put a face on general aviation for their parents. We’re under enormous threat. Our small airports are under threat from real estate interests. Frankly, municipalities are interested in a quick fix for their tax base. I think very few people have a complete and true understanding of the economic advantages of small airports and the safety factors involved with having small airports up and running. There is such a strong constituency in response to noise and perceived danger that is largely uninformed and misguided by those, excuse me for saying this, special interests that are competing for the ground these airports are on. So, I think it’s great to be able to expose kids to an opportunity which is exciting and interesting and which engages them in the educational process. Certainly, there’s a lot of freedom involved, but there’s a great responsibility, too, and if kids see that and see people taking both the freedom and the responsibilities seriously, I think it’s a great example for them.

CC: Do you like to fly at night, or during the day, any preference?

HF: When I’m traveling I fly at night all the time. I don’t really have a preference, but I enjoy flying at night.

CC: Do any of your children like to fly?

HF: Not yet.

CC: You would think some of them might catch the bug. It’s contagious.

HF: It is contagious. It also takes a lot of time, and it takes a lot of mental energy. It’s a real commitment. My older kids have growing families, and my middle set of kids who are 21 and 17, a boy and a girl, are really interested in other things. I have a 7-year-old at home now, who I think may someday get the bug, but that’s a bit down the line for him.

CC: Does Calista like to fly with you?

HF: She does. She was a nervous flyer when I first started flying her. She was a nervous commercial passenger. She very quickly learned to love flying in a small airplane.

CC: There’s nothing like it.

HF: Yeah. That’s true.

We chatted a while longer with Harrison and his brother. The weather did not cooperate enough for anyone to go flying. It was quiet. There was no one else around, a sense of solitude, and you get the idea that he’s not unlike millions of others who like to putter around in their garage by themselves-he’s just got a more interesting garage than most.