Walter Hughes

Published Issue: Winter 2008

The survey was not scientific. It began with a dozen or so friends gathering in the comfort of Spataro’s amiable cocktail lounge. The distinct tastes of the parties involved ranged from fancy drinks that would have been served with umbrellas on warmer days to cheap light beer.

I’m not quite sure who first posed the question, “What is the greatest western ever made?”

All I know is that whatever else we were talking about fell to the wayside and the argument began with an equal mix of volume and competing certainties.

At first there was some disdain voiced for cowboy movies in general. It soon became evident, however, that the excellent 3:10 to Yuma with an Aussie lead, and an actor who lost himself as Batman and a metrosexual serial murderer running back-up, was popular with the group.

It just wasn’t enough to be considered one of the greatest westerns of all time.

We got past the comedians who insisted the genre breaking Blazing Saddles deserved consideration. It didn’t wash. A great western has to be serious stuff, real, or at least what we think might have been truthful, strong and dramatic. This meant the wonderful Cat Ballou, made in 1965 with the brilliant dipsomaniac, Academy Award winner for the film, no less, Lee Marvin, and a surprisingly facile comedienne, a very youthful Jane Fonda, also did not make the grade.

Some comedy was deemed okay.

That allowed Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid to just miss reaching number ten on the list. The movie made Robert Redford a star, and cemented Paul Newman as an okay-to-age, blue-eyed icon who has the humor and swagger of what used to pass as American grace under pressure...the two big questions, of course, are why did they only make one more film together, and couldn’t Hollywood have found something of substance as a follow-up for the exquisite Katherine Ross?

The tenth spot went to an elegiac William Wyler movie, “The Big Country,” a moody agoraphobic nightmare of a misplaced sea captain trying to make his mark in the vast West. Charleton Heston is a bad guy with whom you sympathize, a working man in love with the daughter of one of the two main families, and Chuck Connors is exactly the creep his later Rifleman character would shoot. Carroll Baker is appealing to the bone as the spoiled girl who draws the main character to the West. Jean Simmons is more memorable as the love interest of Spartacus, but her poetic grace and ethereal voice is not lost on anyone. The star was supposed to be Gregory Peck. He does fine. You would invest in him. His lonely fight with Heston in the idle of the night is bruising, and gives some substance to the rumor that the movie inspired the iconic television show Bonanza. The most memorable character in this epic of two families battling for water in the middle of a billion acres is the trashy hard ass, Burl Ives. This mountainous, cruel, crude echoing villain of a man was good enough of an actor to win an Academy Award for this film and smart enough in subsequent projects to bring the difficult writer Tennessee Williams to the masses. Perhaps surprisingly to those who watched his movies, he was also an appealing folk singer and even provided the voice for family Christmas cartoons. Look him up, and imagine him angry and saying, “It will be a frosty Friday before you ride into my valley”...you won’t mistake his intent, and brave bastard or not, you’ll keep your distance.

Number nine was a tie. We lumped all of the obviously great westerns that make the list as groundbreaking films together, mostly because they are old chestnuts that are the cinematic equivalent of reading a classic novel you know would be incredible if your attention didn’t keep drifting. Okay, let’s not argue, I got enough of that from the comedians.

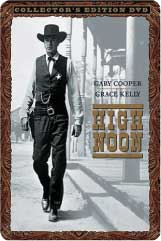

Stagecoach was filmed almost seventy years ago as a horse and buggy road picture. Yes, it has all of the requisite characters who made the West interesting, and it is obviously significant for the starring role played by Glendale-raised, recent USC star, Marion Morrison, turned John Wayne. You get a sense, however, the old film will snap in half at any moment and the reel will keep rolling on a white screen. At least two attempts have been made to update the story, both of them failed miserably. High Noon is dusty, and the town about to be visited by a killer with vengeance on his mind is populated with people who are so weak or corruptible you wonder how they ever got their wagons past St. Louis. Gary Cooper is laconic and righteous, unyielding might be another description, and you know the minute he leaves town with the strikingly pale Grace Kelly, that she’s going to start bitching at him for keeping her out in the sun and never telling her what he’s thinking. The music comes from Tex Ritter and is a reminder that a great Western has a tone. Shane is famous for sound advancements, and there’s no doubt you feel like you are someplace where the mud is muck and goes to the core of the earth. Jack Palance is carved from the same cold stone of the devil’s trident, and when he speaks a flame being frozen comes to mind. The gunfight you keep waiting for does not disappoint, and the kid, famous for yelling “Shane” as he traces the hero’s path into town is a good kid who doesn’t look or sound like a child actor...poor guy, grew up to play Paul Newman’s younger brother in the stunning ‘Hud,’ a modern story of the West, but not a western, and is killed very young in a car crash. ‘Shane’ is the best of the movies you are required to like. I did like it, too, yet I still can’t forgive the director for having Alan Ladd ride up in a pair of buckskins instead of the novel’s descriptive gunslinger black that is dirty from the time he’s spent trying to leave his life behind.

Red River...John Wayne is Ethan...you have no doubt he could ‘build him a place that goes farther than the eye can see’ and is run by tough men who bend to his will. Walter Brennan is good in everything he does and that is true here, too. Montgomery Clift, who must have been either the Tom Cruise or Hugh Grant of his day, is more beautiful than most of the women you see in any picture. It is amazing that years later he will be cast as the doomed boxer in ‘From Here to Eternity,’ because you don’t believe for a minute he could actually beat anyone up, and yet he does, including John Wayne, in an almost movie-ruining scene the Duke must have needed some drinks to forget...who’s the toughest cowboy...hey, John Wayne is the best, period, don’t even question it, but there’s no way Clint Eastwood would ever let a little Broadway actor kick his ass.

Number five is The Wild Bunch. The liquor and hard living had hardened the features of former golden boy, William Holden, by the time it was filmed in Mexico by notorious bad guy, Sam Peckinpah. Robert Ryan, an under-rated and mostly forgotten actor, was believably strong, and he and Holden are completely credible as being tough enough to live with the meanest sonsofbitches in the harshest of places under the worst of conditions. Unlike movies that stretch out fight scenes like the director is being paid by the bullet, the action in this movie makes you duck. There was a lot of discussion of The Magnificent Seven being just as good. The difference is that the former felt like a mean travelogue, while the latter, populated by screen idols, seemed like a revenge film where you cheered for the inevitable end. Some mentioned The Professionals, a film by the corrosive Richard Brooks and starring another great team of actors in search of a kidnapped woman who actually wants to stay with her kidnapper. There’s not a man on the planet who wouldn’t sell at least a part of his soul for a trip anywhere with Claudia Cardinale. UCLA’s Woody Strode holds his own with Burt Lancaster, Robert Ryan, and Jack Palance, but the most biting line comes at the end when a constantly drunk Lee Marvin says cryptically that some men are born bastards and others choose the role.

The Outlaw Josie Wales is the best of the younger Clint Eastwood movies, and the savagery of the post Civil War era displayed makes us wonder how the states ever became united. High Plains Drifter is a moody piece about vengeance and redemption. Of course, the only problem with ranking Eastwood films is that he became such an epic producer and director that his most recent films make everything pale in comparison. He is both John Ford and John Wayne.

There are not a lot who would give Fort Apache such a ranking, but it works here as both a tribute to the many films of John Ford, and a movie that made a mockery of propaganda. John Wayne is measured as the better man of lesser rank. His restraint when confronted with the megalomania of a supremely arrogant Henry Fonda gives you another idea of why the military gets into trouble. The isolation of the fort is relieved by a lovely teenaged Shirley Temple who might have been believable as a young lover since she would soon marry, unhappily, unfortunately, her co-star, John Agar. The hokey ending still works when Wayne, and because he says it you believe it, offers the name of a hero we will never forget...still forgotten by everyone except pedants and film buffs...I’d tell you who he is if you’re interested, but I can’t recall...well, anyway, the other movie mentioned with ‘Fort Apache,’ was the almost as good Rio Grande, made two years later by John Ford, and also starring John Wayne, this time as the quiet suitor of his ex-wife, Maureen O’Hara. The location is the same, another fort, and the action centers around the parents worrying about a young soldier, the son of Wayne and Sullivan, who has left West Point and volunteered for duty in the West. John Wayne is subtle, an actor who should have been given his due award long before the Academy gave him an Oscar for True Grit.

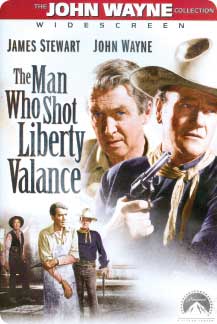

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance...the evil is real, the bully, the drunk with guts and no values, a man who destroys what he can’t become...Strother Martin is Liberty’s gunk-toothed buddy, a screeching, wheezing ugly little man who perfected that particular role until years later he uttered the memorable line, “What we have here is a failure to communicate,” in his tyrannical, genius performance in Cool Hand Luke. James Stewart is magnificent, an actor who manages to say as much in his expressions as he does with his slow drawl, and John Wayne is vulnerable and brave, heroic as the inherently good man who is born to stay a small-town stolid. Vera Miles is arguably stronger than her husband, a steady, loving, equal partner in the settling of America. Woody Strode and five-time Academy Award nominee, Edmund O’Brien, remind us that decency was at the core of the West and the foundation upon which the country was built. The surprise twist, especially the filming of the different angles, has not been done more simply or more effectively. I have never met anyone who did not love this movie.

Tombstone is a movie that seems to get better as we start believing that something being made in our time can be a classic. It is a mystery why Kurt Russell does not get recognition as one of our best actors. He defines what it means to be the moral center of a movie. We won’t even discuss the other Wyatt Earp film that Kevin Costner did at the same time, although we will say that forty-seven years earlier, Henry Fonda and Victor Mature starred in an enjoyable film with the same characters, a thoughtful character study, called My Darling Clementine. Tombstone is filled with rich performances-a fat Billy Bob Thorton as a bully who gets his comeuppance; a cowardly and foolishly dangerous Ike Clanton; a band of craven bad guys who think nothing of raping a bride on her wedding day and shooting a priest, a tormented Johnny Ringo, and Val Kilmer giving perhaps the best performance ever in any western, as the diseased lunger, Doc Holliday. I have no idea what he’s talking about when he mentions huckleberry and daisy, but it works wonderfully, and he never veers from his unique and absolutely compelling characterization of the tubercular dentist. The love story might fall a little short, and there is a false moment when Wyatt and Doc shake hands while riding a horse, but the writing and the acting is extraordinary, even if we’ve known all of our lives how the story ends. Shoot, the ‘Rocky moment,’ when the music swells after Kurt Russell says he’s coming after the bad guys and he’s bringing hell with him, works like it is being done for the first time.

The Unforgiven is flawless. Our group argued about the spaghetti westerns Eastwood made, and how much they were enjoyed was open to wide opinion, the most insightful of the group saying the movies were like training films for what Eastwood has done since he began hitting his stride at sixty years of age. Sergio Leone may have had a great European rep, and he reined in no one less than Henry Fonda at his quiet best for one of his stories; still, mentoring and devotion aside, he’s no Clint Eastwood. The Unforgiven, the Best Picture of 1992, manages to make real and bring to life all the cliché characters of western lore. The gunfighters are more dangerous, real people, incarnated with foibles and dreams, the whores may have hearts of gold, but you get the lesson bad things are caught from lying down on their beds. The Eastern writer telling the story is insinuating and unctuous at the beginning. He is too scared to understand Eastwood at the end when the old killer promises to massacre anyone in his way. It is a tribute to the writing that we are holding our breath when Eastwood’s William Munny disappears into history. I’ll also go on record right now as saying I want to grow old with Morgan Freeman. I don’t know how old he is, but he needs to stop adding any more years until I begin combing gray hair. He’s just so easy, a role he did again with Redford in “An Unfinished Life” and kicking the bucket with Jack Nicholson...sure to be patient whether I’m running to church or asking if we need to shoot someone before getting a beer.

We missed some good ones. Dances with Wolves got as many positive votes as negative reviews. Like all of Kevin Costner’s films there was the complaint that it was far too long and indulgent, and his styled haircut was cited as proof of his on-screen vanity. Even more peevish was the hit that the good and bad characters were lacking any gray area. He might as well have assigned them hats. All I know is that every time I come across this movie on television, I watch it.

The Ox Bow Incident, made in a war year, 1943, could have cracked the top ten. Again, the problem was the good and the bad were handed to the characters more for debate than development. Henry Fonda is us if we were sure to be good under duress. A young Anthony Quinn is terrific as one of the men unfairly hanged in an obviously bad circumstance, and the familiar Harry Morgan, from Dragnet and MASH, is at the beginning of his everyone’s buddy routine.

The Searchers, with John Wayne and Natalie Wood, gets special attention. Some in the group said the movie about two men searching for a young girl kidnapped by Indians was their immediate favorite. They cited its position as the first western and the twelfth film listed in the AFI’s review of the 100 greatest films, and said conclusively that it was the most intense acting in Wayne’s long career. Others insisted the movie is an example of the racism and patronization that was acceptable in the Eisenhower era.

All of the movies are on DVD. I only wish I hadn’t seen any of them, just so I could see them again for the first time.