Written by Terence McHale

Published Issue: Summer 2011

The Old Man

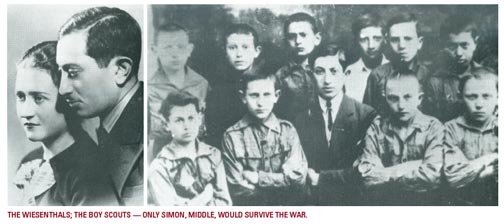

The picture was taken twenty or so years ago at a fundraiser. My friend, Cliff Berg, and his wife Debbie are in the photo. The third person is an old man. His features are drawn long, and his dark eyes are damp. His complex face is weighted down by experiences that never leave him. He has become a celebrity of sorts for the oddest of reasons. The old man survived the Final Solution, a twentieth century idea of inexplicable evil, a plan created to kill all of the Jews in Europe.

The old man lived long enough to cast a bright light on those who participated in the implementation of the Final Solution. His idea wasn’t complicated. He wanted everyone to know that decent people were dragged into a hell where every part of their lives was shattered before six million of them were killed. The old man wanted everyone to understand that their neighbors bought into a society where families could be violently removed from their homes. He wanted everyone to remember that families were stripped of their possessions and sent on trains to terrible places where they were separated by everyday bureaucrats with the authority over life and death. And he wanted those who were responsible to be held accountable for their crimes.

Rabbi Meyer May, an interesting man, explained that this old man would identify officers and guards at the camps who had killed people. The old man would say that it was murder, it wasn’t war. “War is when you are on the beach at Normandy and you’re being shot at and you shoot somebody else, that’s not called murder,” May said. “That’s called war, because that is the nature of war. What we’re talking about here is murder…about people being herded into a ravine and shot. We are talking about guards beating people to death, or hanging them, or forcing them into gas chambers. We cannot accept that there is a scale to murder. There is not something that says genocide and big murder are bad, but little murder is okay.”

After the war ended, the old man’s goal of telling the truth should have been an easy task. It wasn’t. No one wanted to disturb a fragile re-piecing together of a new world order. It was easier to say those times, the years of chaos that made up an era of war, the trips on the train while the rest of the world was bleeding, were an anomaly and needed to be forgotten.

The early days of what ultimately became the old man’s life’s work were solitary. He strung nickels together to finance chasing down soldiers and employees who handled the logistics of murder being managed on a massive scale. He worked by himself. It would have been much easier to quit and disappear into the quiet comfort of a private life. “You are becoming a lightening rod,” he was warned. He kept moving inexorably forward. He had seen too much to let those who were gone be forgotten.

This old man lived a life that was unimaginably different from what his parents could have hoped when he was born early in the last century, in a city that is gone, in a country that no longer exists.

Young once, only for a short time, even a bit of a dandy in the way he dressed and slicked back his hair; he wanted to be an architect. He was denied admission to the university of his choice because of his faith. It was not the first limit imposed upon him. He’d been beaten by soldiers when he was a child. There was no recourse. The soldiers had free rein to be as abusive as they wanted to be. It was an entitlement too many found too easy to indulge. The old man and those he loved were forced to wear a distinguishing symbol. The pogroms in memory were still real and new ones were now more inevitable than considered possible. The legal structure promised in Mein Kampf, and left unchallenged until it was too late, subjected him to fearsome abuses.

The old man’s talent survives him in drawings that are archived, and, had the tenor of his life been different, his artistic abilities were what would have made him noticeable. He fell in love and married his high school sweetheart. That is not a distinction that separates him from millions. It was the way he would prove himself resilient that makes a difference. He was old in the picture with Cliff and Debbie. He got old fast and was old for a long time.

In 1938, a popular short plug shown before the American movies warned the world of the continuing horrors emanating from Germany. The old man in the picture knew of them. He was the hunted in an age of systemic anti-Semitism. By 1939, in a civilized part of Europe, in a modern world, it became illegal for him to drive a car or own property. It was socially acceptable to do much more than break his windows or destroy his business, or beat him up and make anathema the manner of his worship. The Nazi evil – ugly, perverse in retrospect and monumental in history, a marketing and political movement that swept away common decency – permeated a continent. The brown boots and the strutting, the magnificently staged rallies, the hysteria, the Arian purity espoused by weakling men, an absurdity that is now so easily caricatured, were capped by a nationalized stiff-armed devotion to a demagogue with absolute power.

The old man in the picture understood that political extremism sold an imponderable cruelty. Adolf Hitler put the world at war on the premise that a future could be built on a personal violence against Jews. He empowered the sycophantic son of a school principal, a harpsichord player named Himmler, to lead the design of the Final Solution. Adolf Eichmann, a door-to-door salesman with organizational skills and, even by the old man’s estimation, someone who lived the life of a family man, made the trains to hell run on time. The old man would play a role in the capture of Eichmann after the war and would note that this common man’s trial would only have made sense to the prosecutors if he pled guilty to murder six million times.

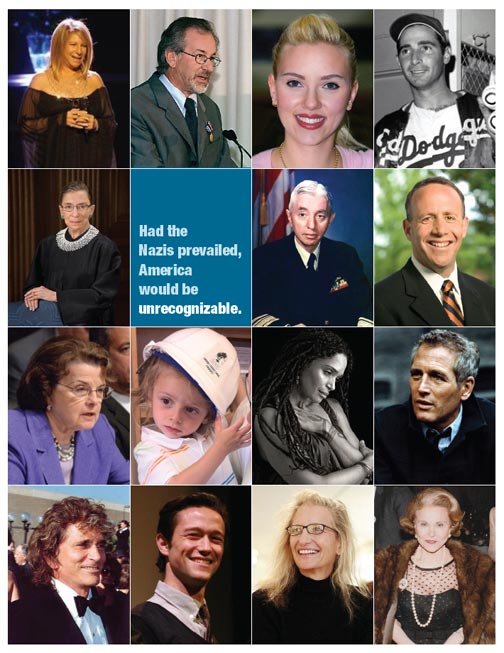

The consequences of a Nazi philosophy can be explained a generation later in gut-wrenching newsreels of a devastated Europe and in the longings of a young girl’s diary. The bombed-out buildings provide a ghostly silhouette. The naked bodies piled in a heap challenge our humanity. The disappearance of Anne Frank resonates throughout the years she deserved to live. She would be an eighty-two-year-old grandmother if there’d never been people, everyday people, neighbors, storekeepers, salesmen, classmates, clerics, harpsichord players hoping to be athletes, who believed in Hitler.

This old man in the picture endured years of captivity. He was brilliant and ambitious and he’d committed no crime.

He was six feet tall, lean, well-built and healthy when the nightmares took over. At the end of the ordeal, and that is all the Allies and the enemies wanted to call the murder of six million people, he weighed only 110 pounds. That is bones. That isn’t being hungry. That is starvation. That is being sent from bunkhouse to bunkhouse where individual Nazis are given the freedom to reduce you until they decide to kill you. He was left in the control of people who worked as plumbers, steelworkers, clerks, and teachers before the war and would try returning to that normalcy when it ended. At one of these insulated camps, the same people who tormented the prisoners as a matter of course constructed a chapel that was visible on the pathway leading to the gas chambers. What benevolent and merciful god did they kneel to in those years? Was it the same god they worshipped before the war and then found waiting for them after they no longer had badges and whips?

The old man was sent to a series of concentration camps, thirteen of them, extermination camps, places of slave labor and everyday humiliations. He lived with execution as a constant threat. Among the millions who would die in a celebrated system of slaughter would be 80 family members of the old man and his wife. He endured the endless deadly minutes of the implementation of a Final Solution that took years to ultimately fail.

The old man would live long enough to chase those who managed to weave murder into public policy.

There is an ancient photo of the old man as a leader of ten other boy scouts. He is the only one who survived the Nazis. The youth before the Nazis took hold of him is completely gone. The young man that once must have charmed and inspired is unrecognizable in an old man who refuses to forget. Where was home he wrote when the war was over? What did the concept mean? What remained of family, friends, a house, relations? None of these existed for him any longer. In the picture with Cliff and Debbie, the old man’s mustache is turning white. His high-domed forehead is a less noticeable feature than the deep folds around his thin hard-set lips.

Everyone at the fundraiser with Cliff and Debbie was there to meet the old man. He survived the wholesale killings. He delineated the difference between vengeance and justice and dared to say, against incredible opposition, that there is a consequence when employees or soldiers turn into monsters. Incredibly, after all it meant for him to be a Jew, a man whose mother died in a gas chamber and whose mother-in-law was shot on a porch in her old age, and the girl he loved was lost for years in the Nazi labyrinth, there was a museum of tolerance being built in his name.

Six million Jews died. He knew them. In his lifetime he also made a point of remembering the gypsies and the homosexuals and the disabled and the noisy, although infrequently heard, political opposition who died because they didn’t fit an Aryan ideal. The Final Solution swept others into the net. He understood what all of them endured. He knew. It is impossible to think about what kept him awake when he went to bed at night.

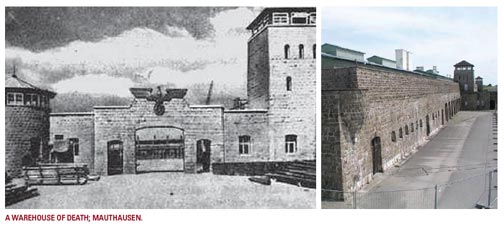

The old man awakened on the 5th of May, 1945, in the Mauthausen concentration camp and greeted the tanks that arrived to liberate the prisoners. It is almost ridiculous to call it a camp. There were 85,000 inmates. Two hundred twenty thousand people died in that tortuous hellhole since it was opened to handle the overflow from the first concentration camp, Dachau, seven years earlier. Can anyone say Dachau now without wondering what was the gossip at the neighborhood market? Who is living in the Berg house? What does a person give up inside to know that Dachau is at the corner?

On the morning that the Allies arrived the old man was punched by a clerk who thought the consistent brutality would continue. It wouldn’t. By the second morning, the lines of power had shifted. The strutting Nazis were reduced. They were emptied of their starched uniforms. They were void of the power over life and death to which they had grown accustomed. The commandant was already on the run. He would die within days and have his body hung on a fence in an ignominious display. Himmler, the harpsichord player turned Halloween architect, would try cutting a deal and find there were no takers. Suicide was his option. Eichmann was running too. The old man would find him.

The old man began a list of the war crimes he had seen the Nazis commit in the camps. He was meticulous. He spent twenty or so days compiling the list in Polish. He was an ill, skinny ghost in a striped uniform summoning testimony from those who lost the grim grasp on the life he still owned. He knew their voice was silenced and he was going to make sure they were heard. The list was done on different pieces of paper for each camp where he lived, and struggled to survive, and the ninety-one Nazis he named became the beginning of his life’s work by letting their crimes be seen in the light. It was important enough of a document that the Allied investigators would save it for evidence. That list still survives today. In the end, the old man would become the Nazi hunter who made justice, not vengeance, his legacy.

The old man is wearing a name tag in the picture with Cliff and Debbie.

Now, long after the villains of that generation have been mostly filed away in a shameful chapter, his name still matters.

The name is Simon Wiesenthal.

Museum

The Museum of Tolerance is an ultra-sleek multimedia, hands-on educational arm of the Simon Weisenthal Center on busy Pico Boulevard in Los Angeles. Busses pull up with kids who like the idea of a field trip. There is the timeless delight of school children out of the classroom and on a break. They are not unlike lines of other kids who are about to enter an amusement park. Maybe they’ve been told that this Museum is not out to entertain them. It doesn’t matter. Until they get inside there is no way to prepare them for their encounter with an age that preceded them.

They are greeted with framed photos of elderly survivors decades removed from captivity. They look like people we’ve always known, our neighbors, our friends, our family, and yet once they were targeted. Underneath their photos are the places they were incarcerated. It is not yet clear that there were almost 1,500 camps, some in Germany, most in occupied countries, some of the names familiar, Bergen-Belsen, where Anne died, Ravensbruk, Konin, Auschwitz where more Jews died than all of Britain lost in the war. In Austria, at the turn of the century, there were more than 240,000 Jews. In 1945, there were less than fifty. There are quotes chosen by the former prisoners of the Nazis; “When I needed to survive, I did.” “Hate is a waste of time.” “Indifference let hatred rule the world, and six million people died.” “My parents never saw their only child grow up.”

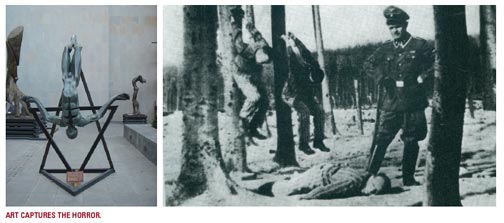

A sculpture, Holocausto, by Jose Sacal, is reminiscent of the way Jews were hanged in the camps. In 1979, Wiesenthal used an actual photo of such an image on postcards that he sent to the German Chancellor asking him to extend the statute of limitations on Nazi crimes. The photo was a stark view of the ease with which torture and murder were part of daily life in the camps. The sculpture conveys what one in six million looks like.

The museum was designed by storytellers. The implementation is high-tech, modern, and hands-on, keeping your attention as you move past screens that challenge you with the power of images and words, to a millennium machine where the seriousness of the field trip is instantly clear in the questions of morality and conscience that are asked and computed. Each of the visitors to the Museum is given the identification of a person who was arrested by the Nazis. It sets the stage for a journey that becomes more personal as you experience all the attendant horrors associated with genocide. It is haunting. There are the personal items that survived. The relics from sacred places are preserved but no longer protected by those families who found peace and hope in the items. You learn about a community, the dancing, the dreams, the worshipping, and then discover it no longer exists. You learn there are many communities that no longer exist. There is the constant foreboding of being chased by the powerful.

You walk through the brick entrance of a concentration camp. It would be trite and unfair to say you get anything close to the same experience of those who were there when such a walk into madness made up real life. It is, however, a vivid moment and the groups of kids who were celebratory outside are now quiet, involved, clearly trying to make sense out of the hatred. Some kids cling to each other. There are tears and there is a wondering how it happened.

Perhaps most powerful is the message that this incredible history would have been impossible if average people did not allow it to happen.

Rabbi May explained that Simon believed the world is made up of haters and anti-haters. “My greatest memory of Simon is when he had just come back from speaking to students. He wanted kids to know that they had a stake in the world, and it is up to them to make the right choices. It is up to you. It isn’t up to anyone else. Every person has to walk out of the museum thinking it is up to me.”

Meyer May

The offices accommodating the work of the Center are across the street in a nondescript building with underground parking. There is the concomitant security that is unfortunately inherent with running a Jewish Center. More than a half-century after the war, the prejudices survive.

The young man who checked my rental car asked who I was there to see. I said I had an appointment with Rabbi Meyer May. He was the first of several employees who told me, unsolicited, how the Rabbi was special to them. An older guide at the museum tapped his chest when I mentioned the Rabbi and said that Rabbi May was in his heart. A woman mentioned how the Rabbi personally cares about everyone who works at the Center. He is a mensch, she said, sure I would know what that meant and happy to convey some good news.

The Rabbi’s office could just as easily belong to a college professor as it could to the CEO of a good-sized company. There are no pictures of the many celebrities he has met over the years, and while there are books, there was nothing pretentious about his collection. I did notice that at the top of a stack on the floor was a private coffee table copy of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s heroic presentation of his years as governor.

The Rabbi is probably in his fifties. He has four lines in his forehead, none of them deep, and he is neither wrinkled nor compromised by middle age. He is nice looking, with hair that is lighter-colored than when he was younger, now gray and balding, and he clearly benefits from his daily walks and clean living. His beard is trimmed, stylish maybe in Rabbinical circles, and also showing the gray. He is friendly, not reserved and not the life of the party, a kindness, immediately good company, a great smile, and a New York accent that has been softened over the years. There is vitality to his movements, intellectual for sure, but more than that; an energy, an enthusiasm that is evident even when he sits behind the desk.

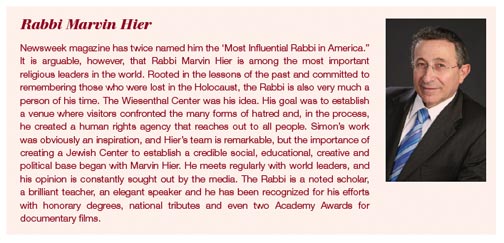

He speaks highly of his more famous colleague, the eminent Rabbi Marvin Hier, the founding dean of the Wiesenthal Center. He gives others credit for the Nazi hunting. Rabbi May is involved in the financing of the center. The Rabbi is officially the Executive Director, a member of a team that has brought more than five million visitors into a museum that seeks to establish a baseline for tolerance through educational outreach, community involvement and social action.

Meyer May was there when the Simon Wiesenthal Center began. He was a young man when he met Simon.

“I knew him when he was a robust person,” May says. “I would pick Simon up at the airport and drive him wherever he needed to go. In those days we didn’t have cell phones. We weren’t texting. We would often eat together. He liked telling stories and had a great sense of humor, sometimes a profane humor. Simon was interesting and would talk of world events. He would talk about cases that had gone wrong, and cases he was working on. He would talk about Israel. His wife asked him why they didn’t move to Israel, why he kept his office in Vienna, and he said the Nazis were not in Israel.

“It is often forgotten that until the Wiesenthal Center started in 1977, Simon was working, literally, by himself. People just didn’t want to be involved with this. At one point he tried to raise five hundred dollars and couldn’t do it. People would say, I’ve been through it, and I want to forget it. That’s why survivors never talked about it for a long time, and from 1945 until 1977, 32 years, Simon worked by himself.

“Simon was not at peace with God after the war. I asked him why. He said, ‘I’ll tell you why. When I was in the Holocaust there was a man who hid a Siddur, a Jewish prayer book. He had a prayer book with him and everybody who wanted to use it had to give some of their rations to this person. I saw someone trade his Siddur for rations that were so meager and necessary. I was disgusted. I said I’m never going to pray again.’ It was a forcefully told story. However, in telling it, Simon also took pause and willingly acknowledged the people who were willing to give up their rations in order to pray.

“Simon lived in places where you see all sides of people.”

Simon

In his own words, in his book, Justice, not Vengeance, Wiesenthal describes the final day of his visit to Israel in January of 1964. He explains that on each trip to Israel he tried to come home with new names of Nazi war criminals that were given to him by Holocaust survivors. On this particular day, three Polish women asked him if he knew what happened to Kobyla.

Wiesenthal explains that “kobyla” is the Polish word for “mare”. The three women explained that there was a female Nazi guard in their women’s concentration camp, at Majdanek, who was given the nickname “mare” because she was always kicking the women prisoners. She was known for carrying a whip that she used to lash and humiliate the Jews left in her charge.

This Kobyla, whose real name was Hermine Braunsteiner, seemed to take particular joy in choosing extra prisoners for the gas chambers. There are stories of her ripping children from their mothers and throwing them up on the back of a wagon.

Wiesenthal spoke often of individuals like Hermine Braunsteiner, a person who would otherwise probably never murder anyone, uncovering their latent sadistic inclinations in concentration camps. They were able to fling a child through the air like a sack of potatoes, strike young girls across the eyes with whips, beat those already weakened by starvation, or fire a bullet into a person’s face.

The Mare

Wiesenthal decided to find Braunsteiner.

He discovered that her family lived in Vienna. He learned that Braunsteiner came from a strict Catholic family and that as a little girl she always dressed up for Mass. The neighbors explained that the family was not wealthy. Her first job was as a maid. Hermine had gone to work as a prison warden during the war. She accepted higher paying jobs at the camps and was awarded a medal for her efficiency. Immediately after the war, there was a tepid effort to deal with the base inhumanity of particularly notorious Nazis. The Mare would spend three years in prison. It was a sentence that she was able to hide from an American serviceman named Ryan. She married him and moved to the United States.

He discovered that her family lived in Vienna. He learned that Braunsteiner came from a strict Catholic family and that as a little girl she always dressed up for Mass. The neighbors explained that the family was not wealthy. Her first job was as a maid. Hermine had gone to work as a prison warden during the war. She accepted higher paying jobs at the camps and was awarded a medal for her efficiency. Immediately after the war, there was a tepid effort to deal with the base inhumanity of particularly notorious Nazis. The Mare would spend three years in prison. It was a sentence that she was able to hide from an American serviceman named Ryan. She married him and moved to the United States.

“During the nineteen years since the war ended there had not been a single Nazi war crimes trial in the USA, and no one had been extradited to another country for such crimes,” Wiesenthal wrote. He thought this legal case looked favorable because if Braunsteiner did not mention her previous conviction to immigration, then there was a legitimate reason to revoke her U.S. citizenship. He hoped a trial would be imminent.

Wiesenthal contacted the Vienna correspondent of the New York Times with information that Hermine Braunsteiner might be living under the name Hermine Ryan in New York City.

New York

In the spring of 1964, there was no such thing as the Holocaust. That name was not yet commonly applied to the openly acceptable Nazi terror against Jews. The Final Solution was considered an anomaly of war. No one was paying attention. The killing of six million ignored the indignities and actual murder of each person in the accumulation of the ghastly number. Even in a country that prosecuted Andersonville, the Confederate prison camp at the conclusion of the Civil War, and hanged the commandant for his crimes against humanity, there was more than reluctance to address Nazi crimes among people living in the United States…there was a refusal. Until Simon Wiesenthal shined his light on Braunsteiner, who was married to an American and living as an American, there had been no prosecution of any Nazi who found refuge i the United States.

Of course this sanguine approach to bloody, cold, muddy brutality was not solely an American sin. There was a point when Wiesenthal couldn’t raise five hundred dollars to search for the Auschwitz doctor who wallowed in depravity, the quintessential Nazi, Mengele, whose last name is such an abomination for his experiments on the most vulnerable, that merely saying it conjures something nightmarish in the way humans can behave.

The assignment to find the brutal Mare, Hermine Braunsteiner Ryan, was given to a rookie reporter at the New York Times by the name of Joseph Lelyveld.

Lelyveld wrote about Wiesenthal and the Mare in a book he called a memory loop, Omaha Blues, in 2005. Forty-six years after he went looking for Braunsteiner, we spoke to Lelyveld, who is now retired after a distinguished career with the New York Times.

“I was a very green reporter,” said Lelyveld. “I was preoccupied in how you do such a thing like finding Hermine Ryan and get her story. I thought it would be immensely difficult, so I wasn’t really worried about her. I was just worried about the reportorial part of tracking her down.

“It was easy, and if I had been more experienced I would have understood that it was easy to begin with. Being an Austrian, she would stand out in the predominantly Irish community in New York. Unless she had hidden out, people would have been aware of her existence.

“I can still imagine what she looked like and what she sounded like. But a clear memory…this is the funny thing about memories; I had a pretty clear memory of the whole conversation and her appearance. Then not that long ago when I went back to my original article, some of what was in my memory was not supported by the article. Especially my memory that when she answered the door, she said, ‘You’ve come.’

“As inexperienced as I was, I can’t believe that if she had actually said that I wouldn’t have used it in my article. Then in my article she was described as wearing shorts and a matching top and holding a paintbrush. I remember the shorts but I didn’t remember that there was a matching top and in my memory it was a feather duster she was holding.

“There was nothing frightening about her. If you had passed her on the street you wouldn’t have seen anything frightening in her. That, I guess, is the whole horror of the Holocaust; perfectly ordinary people turning into psychopathic killers.

“I know nothing about her origins. She was very young when it happened. She wasn’t so old when I met her. To me, the war seemed a long time ago at that point but it was less than 20 years before. I imagine she was in her early 40s when I encountered her.

“The assignment came to us from Vienna, and the story of Hermine Ryan had been passed on to us through the word that Simon Wiesenthal had knowledge of her whereabouts. It was an extraordinary experience, but I don’t believe it was any personal achievement on my part. It just fell to me as an ordinary matter of a newspaper assignment. It wasn’t a great feat of reporting for me to have found her. It’s nothing I feel proud about. It’s just one of those amazing things that can happen to a journalist in the course of a day.

“I do know that I wrote in my own book and in my own memory of the occasion something to the effect that even by the standards of extreme cruelty in those days, Hermine Braunsteiner Ryan went beyond it in her ferocity. According to some of the materials I found during my later research, and I’ve never looked at the transcripts of her trial, that does seem to be the case. She seems to have done some monstrous things, which raises an interesting moral question about whether there is any redemption for a person who does monstrous things.

“My father was a rabbi, and I don’t have any easy answer for that kind of question. I do believe it was good that she was extradited from the United States and convicted in a German court and that she served time in Germany. Of course, there is no justice in these matters. There can never be any justice. I know their efforts continue to find the last 85-year-old killer and to reclaim some piece of property for families that were almost wiped out by the Nazis. It’s so hard to disapprove of those things, but they seem so paltry in comparison to the wicked deeds that were done, that they are just footnotes.

“There is no such thing as restitution in regards to the Holocaust. There is just a playing out of the story, and one day very soon there will be no further playing out of the story because there will be nobody left alive who was directly involved.

“But the thing will still remain.”

The Thing Still Remains

It would take nine years to extradite Braunsteiner. During her trial, which she shared with fifteen other Nazis, one of the longest trials in history, witnesses would tell of the vicious beatings and how the woman who tried hiding as a housewife in America, kicked inmates to death with her steel-toed boots. She would be found guilty of murdering and collaborating in the murders of more than 1,000 people, including 102 children. The testimony in a sterile courtroom of her throwing children by their hair onto trucks was the detail of real moments for the women put in her charge. The stories of her cruelty make you wonder what died inside the Nazis that allowed them to make such behavior a matter of course. Braunsteiner would be sentenced to prison on June 30, 1981, four decades after her crimes were committed. She would receive the mercy she denied others when she was released for health reasons fifteen years later. She died a free woman at the age of 79.

Simon Wiesenthal’s greatest fear was that ‘the monotony of horror’ would become too much for people to take in, and possibly even emotionally digest. Simon wrote, “Sometimes I am seized by the fear that teachers and children in history lessons will be saying in the 20th Century Hitler tried to set up a great empire in Europe. Contemporary witnesses maintained that he had attempted to exterminate the Jews of Europe. There is talk of the poisoning of Jews in specially established camps. It seems excesses were in fact committed, though those accounts are probably greatly exaggerated.

“We are under an obligation,” he continued, “to make young people realize how unique, how unbelievable, how exceptional the period of the Holocaust was. By this very attempt, we make it difficult for them to accept our accounts as the truth and as facts. The incomprehensible remains incomprehensible.”

There is no way for reasonable people to understand an ideal that would legalize and promote the imprisonment and murder of millions of people. How do we make sense of the individual actions that ended the life of a beautiful young girl and countless like her, the unrestricted brutality visited on neighbors, depraved conditions that were part of a master plan, a final solution, a visit by a Nazi officer that was celebrated with the shooting of hundreds of Jews. How do any of those who participated ever find their soul again?

The reporter, Joseph Lelyveld, struggled with the idea of redemption. Rabbi May said, “In Judaism we call it repentance. A person can repent. They can repent up until he or she dies. But does Eichmann ever have an opportunity to repent? Does a mass murderer have an opportunity to repent? Does a small murderer have a chance to repent? It is a difficult thing which would require an extraordinary, serious commitment by the person to change their life. But only G-d has the ability to accept the penitence and to know the penitent’s true remorse.”

The Rabbi took a call from his daughter-in-law at the conclusion of our meeting. He asked her if his grandson was playing basketball and if he had his guitar. He smiled broadly when his grandson got on the phone. He said to the little boy, “I love you. I love you like Craisins.”

In Hitler’s world, and the world of the average men and women who followed him, the Rabbi would be gone.

Simon

Simon lived a long life. He died at the age of 96 on September 20, 2005, in Vienna.

“I don’t think Simon ever became a person who prayed three times a day,” said Rabbi May. “He did not keep Kosher, but he had a connection to Judaism. He was buried in Israel. He wasn’t cremated. He was buried according to Jewish law. So, no hanky-panky. No short cuts. I don’t think he was angry at God by the time he died.”

In the picture with my friend Cliff and his wife Debbie the old man who had done so much is wearing a name tag.

There is a remarkable museum that bears his name. And those he wanted remembered will never be forgotten.