Written by Terence McHale

Published Issue: Winter 2008

On April 30, 2001, 53-year-old Congressman Gary Condit is sitting opposite President George Bush when the topic of the crippling energy crisis in California is raised. Bush, barely three months in office, tells Condit to take up the subject with Vice President Dick Cheney. Condit says Cheney is refusing to meet with the California democratic delegation.

The Vice President will meet with you is the President’s answer.

The following day, May 1, 2001, Condit and Cheney meet privately at the Capitol. There is no resolution on energy, but the discussion covers other topics, such as the new University of California in Condit’s district and the controversy surrounding the Endangered Species Act.

Gary Condit, a California politician who combines enormous personal appeal with a longstanding political base, is on a roll.

Although he typically eschews any titles, Condit is the founder of the Blue Dog Democrats, a moderate group of twenty or so legislators from around the nation who smartly keep a limited agenda and sway the outcome of critical legislation before the United States Congress.

In California, he is the first in their Congressional delegation to have endorsed his former classmate in the Assembly, Gray Davis, for governor. He is largely viewed as not only the Washington conduit for Davis, but a rare friend so closely allied that Condit’s son and daughter are given jobs in the Administration that keep Gray and Gary in close contact.

Condit is a steady political partner with Nancy Pelosi, a beneficiary to the political fortunes of his former seatmate in the California Legislature, California State Senate President pro Tempore, John Burton. In 2001, Pelosi is on course to become the first woman Speaker of the Congress.

His home district in Central California is popularly called Condit Country. His constituents call him Gary. They encourage his independent streak with landslide margin election victories and polling that reveals he would be equally successful as a Republican or Democrat, prompting him to borrow a friend’s joke that he’s been invited by both parties to switch. His son, already a go-to person in the State Capitol, is in line to inherit an Assembly seat. A protege who will soon disappoint him is being handed a State Senate slot.

Condit, a preacher’s boy from a small town and never very comfortable raising money when he knows personally what it was like to make it, opens a Political Action Committee. It stokes the talk of him running for a statewide office. A young fundraiser for the Assembly Speaker, Dan Weitzman, remembers being at the elegant Sterling Hotel in downtown Sacramento when he sees Condit for the first time. Years later he offers the observation that Condit was an imposing figure.

“Everyone stepped back and just looked at him when he walked into the room,” Weitzman said. “He had incredible presence. He was alone. I was hearing some very ambitious politicians say Condit would be unstoppable if he ran for Lieutenant Governor or if a U. S. Senate seat opened up.”

On the day he is meeting with Vice President Dick Cheney, Condit is a half step away from becoming one of the most influential individuals in the country.

Across town, a young woman thirty years his junior is leaving a Washington internship and returning to her home in Condit’s congressional district. She is on her computer looking for places to go before she catches a plane.

Her name is Chandra Levy.

OKLAHOMA

The Tulsa area in 1948, the year Gary Adrian Condit was born, was a hard, dry place still living with the dust and poverty of the Depression and a memory of the Dust Bowl Diaspora. It was built alongside nature’s Tornado Alley and was subject to all the extremes of bad weather. The late Franklin Roosevelt was still a hero, the four-times elected Democrat who brought America out of economic despair and through a world war, authored in the New Deal to get people back to work.

The Condits were dairy farmers until Gary’s father was called to the ministry and sold the farm to an uncle. It happened when Gary was a ‘little guy.’ Church was a mainstay of their lives, singing and worshipping during the week and on Sunday, a lot of old time religion for Gary’s two brothers, one older and one younger, and their baby sister.

Condit did not let churchgoing interfere with him trying to have more fun than anyone else. He carried a fake ID. He admits to being a wild kid, saying matter-of-factly that he liked drinking with the guys, partying, and enjoying himself. His stories are nicely told, folding out like a Huck Finn chapter, a slice of Americana, a time that is already gone.

Going to church was all he got for free. Gary was expected to work.

“In my older teens,” he explained, “I lived in a house by myself in the summer. I would get up early to work as a roughneck in the oil fields. Sometimes I’d be a welder’s helper. Sometimes I’d be on a truck or a backhoe. Sometimes I’d move up to oil drilling. It was a tough place. The guys on the pipeline would stop their job at a moment’s notice if there was a fight developing and, unlike school, the fight doesn’t get broken up until the fight is over. The oil fields taught me to keep my mouth shut and fight if the situation called for it.”

CAROLYN

Carolyn Berry was a store owner’s daughter. Her parents owned several clothing shops on the right side of town. She was one of the popular girls in school, born blessed with a mid-western beauty, a picture of health, a facade of sorts since she contracted a fierce case of encephalitis when she was ten years old. The disease is a recurring inflammation of the brain. Her parents had the resources to get Carolyn the best treatment. The illness is stubborn and will remain a consequential problem her entire life. Carolyn is Catholic. She belongs to the pep squad, a sporty girl, the kind of girl who develops lifelong friendships and close family ties. She and Gary fall for each other. There is youthful drama to them. Both blonde, attractive, driving too fast in the car Gary purchases with his oilfield money. The easy story is that of the wild boy stealing the heart of the good girl.

Carolyn doesn’t remember it that way.

“Gary was fun to be around,” she said in a recent interview with California Conversations. “He didn’t fit into any group. He worked. He was smart. He was someone people wanted to be near. I was in love with him when I was fifteen, and I love him still.”

CALIFORNIA

Gary and Carolyn married at eighteen. They followed his parents to Ceres, California, a small town of middle class neighborhoods about 100 miles east of San Francisco. She admits being scared about the move. Her friends keep saying she can come back home if it doesn’t work out.

Gary remembers the whole of California’s Central Valley being connected to Oklahoma, Texas, Missouri, Kansas, a lot of second-generation people. His grandfather was living in San Simeon and there were many vacation trips along Route 66 to visit him. During tough times in Oklahoma, Gary’s grandfather harvested California fruit.

Gary and Carolyn were still teenagers when they become parents.

“Gary quit drinking when Chad was born,” Carolyn says. “He didn’t make a big deal out of it; never made any kind of announcement. He just stopped.”

Condit remembers, “I saw Chad and I knew right then I had to hunker down and do things right. It had nothing to do with religion. It had nothing to do with any kind of alcohol problem. It was simply a decision I made, and I have never regretted it.”

The young couple rent a small home. You can get a clean and comfortable place for a couple hundred dollars a month. Gary works full-time at a variety of jobs to put himself through college. Carolyn is a stay-at-home mom. There is still the possibility of returning to Oklahoma and going into business with Carolyn’s father.

RUNNING FOR OFFICE

Politics was not an obvious option for Gary Condit in 1972. First, there was his age, he was only 23 and still a senior at Stanislaus State. Second, he was not much of a joiner. Friendly, he was not terribly outgoing, and he and Carolyn had only been in town about four years. Third, he’d never been involved in the political process.

“I worked at Norris Industries making mortar shells for the Vietnam War,” he said. “I’d go to school from 8:00 in the morning to 1:00 or 2:00 in the afternoon and get to work at 3:00. Initially, I didn’t think much about it, but because I was married and we had a child my classification for the military was different. I drove to work with an older gentleman whose son was in Vietnam. At one point during a contract negotiation, it looked like they were going to lay people off. This gentleman said, “Oh God, I’m going to hate it if I lose this job.” I called him Stringbean. I said, “Stringbean, you have a son in Vietnam. You should be happy if we lose our jobs and he gets home safe.”

“I understand people’s need to have a job and it was a good job, but this war needed to be over. That conversation planted the seed for me thinking I needed to do something to prove young people wanted to make a positive difference. I eventually decided to run for city council even though I had never been to a city council meeting until the night I was sworn in.”

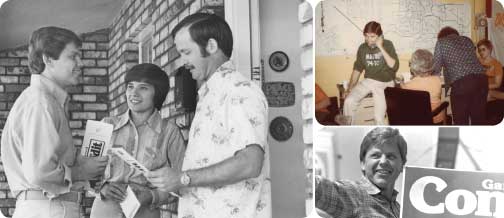

It took 1,300 votes to win a seat on the Ceres City Council. Condit spent $67. He managed to get a small army of students to help him run a door-to-door grassroots effort.

“I went to work election night. When the polls closed, they opened up the back of the machines and by 8:05 people at my house knew I won. They began calling to say you’re in tenth place, but it looks good. Then they’d call back and say you’ve moved up to eighth and then seventh and then sixth. I’ll never forget it as long as I live, the manager and the people with whom I worked, they were so proud of me, they said this is so cool that you ran...They said how’d you do? And I said I think I came in sixth, but that’s pretty good, don’t you think?”

Carolyn laughs when she remembers the joke. There were hundreds of kids in their small house and front yard yelling and screaming when Gary got home. He said thank you to every one of them. She did not remember him giving a speech.

There were national stories about Gary being one of the youngest elected officials in the country. He and Carolyn quickly became a recognizable couple in Ceres. His election was not a lark. Condit did more than dress the part, although he became more stylish, he paid close enough attention to the job that two years later he was mayor.

Tom Berryhill comes from a longtime Ceres family. He is a Republican whose dad ran against Condit for Congress. Tom now represents the area in the California Legislature. “Gary Condit always had great rapport with the people he represented,” Berryhill says. “Until the day he left office, his phone number was listed. Gary has a quiet way that goes beyond charm. People trust him. They wanted to be on his team. Even now, he is the model of the kind of politician I try to be.”

Condit’s youthfulness became a punch line. There is a story from the local Rotary Club about board members from a major company wanting to do business in Ceres. They asked to meet with the mayor and, seeing Condit behind the desk, asked if it was Mayor for a Day; the cherubic Condit making them wonder if he was a high school student.

In 1976, Condit steps to the head of the political line and becomes county supervisor. Six years later and not yet 34 he goes to the California Legislature, the Assembly class of 1982.

THE ASSEMBLY

The Speaker, Willie Brown, said he knew the future leadership of California would come from the class of 1982. Condit had no doubt that his intense classmate from Los Angeles, the very focused Gray Davis, a former Chief of Staff to Governor Brown and an indefatigable fundraiser, would be governor.

Condit began a close friendship with four others, three of them in their late twenties and early thirties; Steve Peace, a mercurial, oftentimes brilliant, sometimes erratic, quick thinking enfant terrible from San Diego; Charles Calderon, an effusive lawyer from East Los Angeles, a pragmatist as much as an idealist, a gentleman, and the first of three brothers to serve in the Legislature; a wealthy and enjoyable Rusty Areias, the son of a dairy farmer and the dark-haired, more accessible counterpart to Gary; and Jerry Eaves, a supporting actor in a gang of stars, a bearded stalwart who looked, acted and was treated like a steady older brother.

“One of the things you find out in politics is after you get onto a city council or in the state legislature or congress, you look around and say I don’t know how that person got elected,” Condit says. “But, I’m telling you, if you pay attention, pretty quick you see how they got elected. Each person brings a skill, something they’ve honed, something they’ve worked on that works well and when you pay attention, you see it come out of them and you go, “Oh, that’s how you got elected.”

A MODERATE IN A LIBERAL HOUSE

Temple Davies, a former fighter pilot in WWII, a 62-year-old grandfather with a son caught up in an ugly divorce, brought Condit the idea for his first bill. Davies’ estranged daughter-in-law will not let him see his grandchild. He tells Condit that grandparents belong in a grandchild’s life.

Temple is 86 now. Two strokes have dimmed the landscape. He keeps a picture in his living room of the Governor and Gary and himself at a bill signing for ‘Grandparent’s Rights’ as proof to his grandkids that he accomplished something important in his life. He remembers being surprised by Condit’s youth when they first met, although in retrospect he says Condit was probably much older than he looked. Davies recalls Condit taking his own notes and quietly asking questions.

“Condit has a very quick mind and a great skill for listening, which is not an easy thing in any profession,” Davies said. “He never talked at me, always to me, and he made the effort to keep me informed of the bill’s progress.”

Temple’s legislation is now replicated in more than forty other states.

California Conversations: Archie Fain?

Gary Condit: From Oakdale...murders a 17-year-old boy, and rapes two girls.

CC: In response to the possibility of him getting out of prison, you write AB 2192.

GC: Right. It allows the families of the victims to speak at parole hearings. It was a tough bill. I also have a side of me in terms of having empathy for people who spend time in jail, but fair is fair.

CC: You also write a new bill aimed at drunk driving...three years probation, and mandatory jail time if you break the probation.

GC: Right.

CC: This was before Mothers Against Drunk Driving.

GC: I don’t remember the full genesis of that bill, but to this day, I have a sense that one of the greatest things that has occurred in this country is Mothers Against Drunk Driving. When I was growing up, you got a case of beer and you went down to the levee. Now, people think about designated drivers.

WILLIE BROWN

By any account, Willie Lewis Brown, Jr. is one of the great characters in California political history.

The clever, charismatic, Texas-born Brown followed a street-wise uncle to San Francisco and made it his adopted home. Elected to the California Legislature in 1964, he would serve the longest tenure of any Speaker of the Assembly, and prior to the absolute timelines of term limits, he faced his greatest challenge when Condit and his four friends, now dubbed “The Gang of Five,” all Democrats, took advantage of a five count difference between Democrats and Republicans in the Legislature to swing votes away from Willie’s agenda and eventually attempt to remove him from his post.

In a California Conversations interview with Brown he says he respected Condit and the others, even thought for a while he was grooming them for greater roles in politics, but the longer he talked he could not hide his frustration at what he called Condit’s conniving. He laughed briefly when it was suggested that the difference between conniving and strategy depends on the alliance. Condit was a conniver, he finally insists. There is no doubt they had a different view of public policy.

CC: In 1984, you’re in Willie’s good graces and he makes you Assistant Majority Leader. You’re the first in the class of 1982 to get a big post.

GC: That’s true. I also found out that this kind of position becomes a burden...you checkmate yourself a little bit because you knew Willie was keeping you close.

CC: You continue your independence - proposing to tax professional sports teams and earmarking the funds for high school athletics.

GC: I still think it’s a good idea...high school sports is a recruiting ground. We’re training quarterbacks. We’re training tackles. They hone their skills, and I’m proud they do, but we’re making money for guys who own the teams.

CC: Maybe we could tax lawyers to pay for the debate teams.

GC: (laughs) It’s a great idea.

CC: 25 years ago-anabolic steroids-you were the first legislator to step up and say these are a nightmare and need to be restricted.

GC: I held hearings all over the state. I debated Lyle Alzado on a radio program, and he was pretty strong. He called himself a pro-choicer on anabolic steroids. I was frustrated when even my hometown newspaper, without ever calling me, editorialized against the bill.

The towering Alzado played for three teams in his fifteen year NFL career. He died at 43 from a cancer ascribed to steroid use. Condit’s relationship with the newspaper would remain dicey.

CC: You came up with the idea to rebate budget reserves in excess of 4%...is that the beginning of you being more conservative or a populist?

GC: Governor Jerry Brown’s administration built up a huge surplus. I believe in a rainy day fund. I also believe tax money belongs to the people.

CC: You and your four friends were all moderates-the Gang of Five-one of the best times of your life?

GC: It was fun-the camaraderie...you know, we didn’t think of ourselves as the Gang of Five. That was a name given to us.

CC: Were the five of you close personally?

GC: Willie made every attempt he could think of to break the bond that developed between us. Every attempt he made only made us stronger, more reliant on each other.

CC: Could Willie have stopped the Gang of Five early?

GC: Let me tell you something no one’s ever written. The Gang of Five started when Willie called me first and said you guys cannot introduce no-fault insurance. You can’t do death penalty legislation or call for electronic surveillance of drug kingpins. Well, we kept doing what we were doing. He called me back and told me if I didn’t put a stop to it that day, he was going to remove me as chairman of my committee. I told him in no uncertain terms that I didn’t get elected to the Legislature to be threatened. I was removed. He let my removal fester. Then he called the others in and began removing them from their committees.

CC: You pushed for limiting the Speakership to six years, knowing that Willie was in his seventh.

GC: The five of us tried to have a measured response to his bullying.

CC: Did it ever get personal?

GC: It wasn’t meant to be personal. Willie’s friends and the press wanted to make it about a leadership fight rather than public policy.

The Gang of Five became statewide personalities. The press was not always good to them, although Rusty Areias says Condit didn’t care and told them not to get caught up in being a hero or a goat. Condit says now it was just his feeling at the time that it always makes sense to keep your mouth shut. Some articles were corrosive, mocking them as grandstanders. Others said their political views reflected the direction the people in their districts hoped the state would go.

The Gang also relished the attention. They took up residence at a main table in a popular downtown restaurant. Randy Paragary, who now owns several high-end places, offers the picture of all of them being young and there being an edginess to their thinking - it was big stuff. They were taking on Willie, who was a big deal, and they were winning.

The rumors of partying became part of the distraction or the attraction depending on your perspective.

A former lobbyist was married to a woman who worked in the Capitol. He was convinced that Condit was having an affair with his wife and confronted Condit. He said Condit was unflappable, and denied anything was happening. Almost twenty years later, he says his now ex-wife has never admitted to an affair with Condit.

The rumors of women were a constant. Areias told the Los Angeles Times a story he repeated to California Conversations - that he has been a close friend of Gary’s for twenty-five years and has never seen any actual evidence of Condit with another woman. Assemblyman Calderon, typically candid, says Condit was appealing to women and they were appealing to him, and while Calderon never saw it himself, he wouldn’t be shocked if something happened. He also pointed out that when Condit’s name was in every publication worldwide and there was an added monetary incentive to come forward, very few women said they were involved with Condit. Condit, he says, had faults. His critics have been disappointed by the fact that all the stories they’ve heard did not turn out to be true.

Paragary has fond memories of all five members of the gang. Condit was not his favorite. The teetotaling Condit was friendly enough. Unlike the others, however, he had a natural reserve, a distance and a space around him.

The Gang of Five seduced the Republican minority to get the needed votes to remove Willie from his Speakership. Brown says now he had Republican votes the Gang didn’t know about. Both sides are excellent at counting and how the final vote would have gone remains in doubt. It became a moot point when an assemblyman named Richard Longshore died the night before the vote was to be taken. The mathematics no longer worked.

“Willie invited me to lunch. And to Willie’s credit, he probably handled this better than I handled it. He said, ‘Look, Gary, we need to bury the hatchet. We need to be friends.’ I said, ‘Willie, we’re not going to run around together again. We’re not going to be friends.’ I had no intention of falling in line. When I left that lunch I knew my days around the Capitol were limited.”

Willie Brown does not dispute the meeting took place. He says nobody’s beyond redemption and while the Gang of Five behaved like assholes he admits to offering Gary a chance to get back into the fold. In Willie’s telling, he says Condit didn’t say a damn thing...didn’t say yes and didn’t say no. He just got up and left the room.

Rusty Areias says Gary’s account makes sense. “Willie is a genius in many ways, including his choice to remove anything he doesn’t like from his memory.”

Calderon explains that one of the mistakes people first make about Gary, especially when they see that big smile, is not realizing how tough he is. “Gary is intellectually and physically one of the toughest people I have ever met. I have no doubt he told Willie what he was thinking.”

Condit says that after his lunch with Willie he expected to finish his term and get on with his life.

Of course, politics is about timing and stealing the moment. Tony Coehlo, a congressman on the rise, whose congressional district crossed over Gary’s assembly seat, got caught up in a financial scandal with financier Michael Milken and resigned. Condit decided to run as his replacement.

Fellow gang member Rusty Areias pretended for a while that he would challenge Condit. Eventually, Areias endorsed his friend and Condit coasted through the Primary.

Areias notes that it would have been easy for Condit to run as an anti-Coehlo candidate, the reformer cleaning up a mess. He didn’t do it. He chose instead to be respectful of Coehlo’s enormous contributions and run on his own record.

His opponent in the General Election was a guy everybody liked, a former legislator who also served as California’s chief agricultural officer. A wealthy, successful farmer, he was a generation older than Condit.

CC: What was Clare Berryhill like?

GC: You have to remember we were two Ceres boys. (laughs) The main competition was who was going to carry Ceres. Clare had folksy written all over him. I found out he was running and I thought, oh gosh, I’m going to have to debate this guy. I liked Clare. I always admired the way he handled himself. I liked him. I liked his boys.

Condit held his own in the debates, probably winning one that he shouldn’t when he and Clare covered agricultural issues before a room full of farmers. His refusal to be labeled served him well, and taught him the lesson that being defined as a liberal or conservative limits perspective, his own and his constituents. Never a barn-burning orator, and not exactly one of the crowd, Condit does have a natural speaking style. There is a slight Oklahoma turn to the end of his words. He stays calm. He doesn’t lecture, a natural reticence that is appealing, and he is just as likely to offer possible solutions if everyone works together than an absolute answer to controversial problems.

Tom Berryhill says the Republican leadership told his dad the only way he could win is to go after Gary for ‘his skirt chasing.’ Clare was reluctant. It was forgotten when their opposition research could not come up with the names of any women with whom Condit had an affair.

CONGRESS

Often named the most conservative member of the California Democratic Congressional Caucus, Condit’s refrain is that he was exactly in the middle when viewed on a national scale.

He is proud of the work he did to bring U.C. Merced to the district. He considers the money he managed to earmark for cops, infrastructure, education, and the battle against methamphetamines to be part of the job and not accomplishments. His role nationally to balance the budget and his appointment to the Intelligence Committee mattered personally. His response to constituent problems was legend and part of the work ethic he ingrained in his Washington and home offices.

CC: Did you like your California delegation?

GC: I loved them. Yeah, there were some I was closer to than others, but…

CC: For such a large delegation, they were surprisingly benign.

GC: I know the delegation gets criticism, but I think they work well. If you look at the Alabama delegation, there are six or seven of them, Republicans and Democrats. They go to the back of the chambers and huddle up and hold hands and say, yeah, that’s what we’re going to do. This instant unity isn’t possible in California. Our state has so many regional issues, and so much diversity, that it creates conflict.

CC: The Blue Dogs - were you the founder?

GC: There were three of us that actually created the Blue Dogs. We were 23 when we started. I learned to keep the group small because we could find consensus quick. And the other thing that we did was to only pick two or three agenda items. We would literally meet for days, weeks and figure out where we have to be to win votes with the Democratic caucus and the Republican caucus.

CC: Your detractors call it back room maneuvering.

GC: It is the nuts and bolts. You can’t get to the core of an issue if you’re making a speech. I learned Ronald Reagan was right when he said you can get a lot more done if you don’t care who takes the credit. You need to give people time to absorb what you want and what they’re willing to give up. If you push them out in public, they’re not going to give up anything.

CC: Was immigration a Blue Dog issue?

GC: No, but I carried a little piece of legislation that was called “Unfunded Mandates.” If state and local governments would simply say to the Federal government, you do what you need to do on immigration, but reimburse us for the incarceration of the prisoners. Reimburse us for health care. Reimburse us for the costs. I promise you if they were forced to do that, they would have an immigration policy in short order. The Blue Dogs endorsed it.

CC: Who is the most intimidating politician you ever met?

GC: I don’t know any politician I’ve been intimidated by, and I’ve met a lot. Clinton had such skills that before the Blue Dogs had a meeting with him, we’d rehearse. We did not want our time to be wasted. Bush had a different spiel. President Bush, the current President Bush, lets you talk. He gives you the impression he just might say, you know, we ought to do that.

CC: Who did you like more?

GC: Well, I was around Clinton more. I liked Clinton a lot. Contrary to what the Modesto Bee and the Washington Post wrote several times, I voted three times not to impeach Clinton. The President will tell you I was one of the first to call him when he was isolated from Congress and tell him not to resign.

CC: Is the country safer with a Bill Clinton or a George Bush?

GC: Obviously a Bill Clinton. His agenda was to keep us out of war. I voted against the war in Iraq because there were no weapons of mass destruction. It is a war based on falsehoods. Sadaam Hussein was a menace, but he was not a threat to our country. During the Persian Gulf War, I had a sit down with George Bush, Sr. He said, look, Gary, I want you to vote for Desert Storm. I said I’m having issues because my frame of reference is Vietnam. He didn’t fudge the truth. He said we’re going to run the army of Iraq out of Kuwait. Then we’re coming home. I voted for Desert Storm.

THE DIFFICULT YEARS

California Conversations met with Gary Condit in a hotel room in Denver for an extensive interview that lasted more than six hours. We spoke several subsequent times on the telephone. He did not ask to see any questions ahead of time. Nothing was off limits. He made it clear when he sat down that he was not looking for redemption.

He is handsome, different than he looked as a young man, much thinner, stronger, almost gaunt, and it adds up to a good look. The physical change began when he made exercise a daily regimen and went seven years fasting every Wednesday. In his first interview in years, he was both soft spoken and direct.

CC: You leave a meeting with Cheney on May 1, 2001. When do you find out Chandra Levy has disappeared?

GC: The meeting with Cheney was on a Wednesday. On Sunday, Chandra’s father, Dr. Levy, calls me at home in California and says he called the Metropolitan Police Department (Washington D.C.). They had not been able to get a hold of Chandra for three or four days, and he knew she’d come to our office. He felt the Washington Police Department blew him off.

CC: She wasn’t missing long enough to…

GC: Technically, that was the police issue. Dr. Levy wanted to know if I would contact the police department and get them to be more interested. I made the call, and I gave them a tough talking to that you cannot allow a father on another coast to think you don’t care.

CC: How does it get from Dr. Levy making the phone call for help to the point someone thinks you killed her?

GC: I don’t know...if it was incompetence on the part of the Metropolitan Police Department or by design considering the way they handled the case.

CC: Were you ever a suspect?

GC: Never by name. I was treated like one. I became distrustful of the Metropolitan Police Department pretty quick because what happened was...I don’t know if you want to hear this...a lot of people think they know…

CC: I’d like you to be candid…

GC: This was never about a personal scandal. This is a missing girl. The next day I flew to Washington, D.C. My staff person said the police are really angry at you for whatever you said to them. On Tuesday afternoon the police called and said we’d like to talk to you. I said sure. We can meet here or when I leave my office about 8:00, maybe 9:00. When I got home, two detectives came by. We spent 45 minutes together, and I told them everything I knew. There was nothing else.

CC: What did they ask you?

GC: I can’t remember all the questions, but everything I knew about Chandra, I told them. I never lied to law enforcement about anything to do with Chandra Levy. By the time this was over, I did a lot more than anyone else would to appease the law enforcement people. I did take a lie detector. I gave them DNA. Eventually, the FBI interviewed every person who had ever worked in my office. They brought Carolyn to Washington and spent 8 to 12 hours grilling her. They couldn’t find anything, but they spent all that time trying.

CC: Did they ask you at that first meeting if you had an affair with Chandra?

GC: No, they did not.

CC: Were they treating you as a suspect at this point?

GC: I was taken aback by the way they proceeded. I was thinking we’ll figure out where Chandra is. You never think anything bad will happen to someone you know. A few days went on, and I have never told anyone this publicly, but I got a call from a network news source. The reporter said they’re going to try putting you in jail. Frankly, I was never, ever scared because I knew the truth. The way I dealt with them was I became more protective. I eventually got legal counsel.

CC: You and the Levy’s put together a reward of $25,000.

GC: I called Dr. Levy once it became evident there was a search, and I said sometimes we’ve given money for getting information. He acted stunned for a minute, and then he said I’ll put some in there too.

CC: At this point, Chandra’s aunt is telling the family you’re having an affair with Chandra.

GC: I don’t know what was going on with their family.

CC: The press is pushing the question about an affair with Chandra Levy?

GC: I did not have a romantic relationship with Chandra Levy.

CC: Are you drawing a distinction between a romantic relationship and a sexual relationship?

GC: It’s none of your business. I mean, if I were to start answering it, well then, how many times did you have sex? All these other women that have been mentioned, did you have sex with them? It just goes on and on. My private life is my private life. If we don’t reclaim that, we’re all going to be designated as public people and we will have no more civil liberties. I stood my ground. I guess people will determine whether that’s correct or not.

CC: The public relations experts I’ve spoken to say if you’d gone on camera early in the story and spoken to the press your later problems could have been mitigated.

GC: This was cast. The press was going to do what they were going to do. I didn’t concede to anyone that it is appropriate to go into the political routine. It’s almost a game now when you see people do it...you’ve got the wife there...the kids there...it’s all props and it’s planned and they poll the effects after it is over. I said then that we should be focused on Chandra Levy. Pay attention to what the Metropolitan Police Department of Washington, D.C. is doing. The sex questions are irrelevant. You have an innocent girl who possibly something bad has happened to, and you’re following me around asking me if I had sex with someone. Why aren’t you following around the police chief, the FBI guys and asking them what they were doing? Why didn’t the police look at the tape of the people entering her apartment building? Her computer clearly had a map of where she was going. They didn’t check it for months. Why? We may never have a full answer.

CC: You are in your fifties. Chandra was in her twenties...do voters have the right, since you don’t speak, to say I’m not voting for him because I’m disappointed in him or believe he had the relationship?

GC: I live by the theory that voters have the right to decide what they want to decide. I also believe there are boundaries public people should stake out for themselves. We should not, in my opinion, deviate too much from those because they just keep probing and probing more and more until you end up with zero. You will have no privacy; your grandkids will have no privacy; everything is free game. I just don’t think that is what getting elected is all about.

CC: What advice were you getting?

GC: I was being told to go in front of the camera and apologize for anything. Look, I understand the Biblical thing that confession is good for the soul, but the press is not the confessional. I had nothing to confess about. I had nothing to do with Chandra being missing. I also had one of the wise men of the Congress, a federal judge walked up to me early on and he said, Gary, everyone here likes you and they are going to try and find out what’s going on in your head. Just remember how much they all like to talk to the media and, in addition, any one of them can be subpoenaed. It was great advice. People may have not understood it, but I didn’t want to drag anyone in. Another Congressman asked me how I was holding up. I told him I had quit watching the news and was following the weather channel instead...that I could give him a five-day forecast for anywhere in the country...the next day his staff person called up and apologized because that quote appeared in the paper. Bob Matsui, the Congressman from Sacramento, came into the Congress one morning and he was white as a ghost. “Gary, I just talked to the Fox people, and they say they’re going to take you down.” He was offended. I’m sure my colleagues were thinking if they can do this to him, they can do it to anybody.

Carolyn responded to a note from one of her friends in Oklahoma that it was a difficult situation. The friend spoke to the press. The details of the note became public.

In August of 2001, Condit agrees to an interview with Connie Chung on ABC television.

CC: Why did you go on Connie Chung?

GC: It was against my better judgment to do it. I did it based on my attorney’s advice.

We had two different agendas. His agenda was to salvage my political career. I was simply trying to salvage myself, my life, my spirit, and my wife. We had options that we could have worked with another reporter. Connie wrote several letters, and they were letters of how fair she was going to be...then the first words out of her mouth were, “Did you murder Chandra Levy?” How ridiculous. I shut down.

Carolyn Condit says with some chagrin that the minute Connie Chung opened with that question she knew Gary was not going to talk any longer. Just an hour before the interview an attorney delivered an envelope to Condit with the request that he not discuss Chandra. Condit says that he would not have done that anyway. The show was a debacle that did nothing to shed light on the loss of Chandra Levy or the personality of Gary Condit.

CC: Who came up with the line “I’m not a perfect person”?

GC: I didn’t lie to anybody. I hadn’t done anything illegal. I was just saying, maybe it wasn’t an apology, but I acknowledged I’m not a perfect person. It was my feeble way of trying to make concessions that obviously didn’t work.

CC: Did you feel your life being destroyed?

GC: Well, I went through some emotional stress and depression over this. Who wouldn’t? What the tabloids do is rape your reputation. They pay people money to tell stories, make up stories, and when you see the covers as you walk by the rack you’re witnessing the rape of someone’s reputation.

CC: Did you see the tabloids?

GC: I’ve seen most of them now. We had a shop in Ceres, a little grocery store, and because of us they moved all the tabloids out.

CC: What was the response when everyday people saw you during this period?

GC: For a period of time I was probably the most vilified man on the planet. People were gawking. There were a few people who would say things, and there would be people who were kind. And there would be people who read between the lines, and they said well this guy’s getting railroaded.

CC: Who do you rely on during this period?

GC: You rely on the family. My family is Cadee and Chad and Carolyn and my mom and dad. You know, it was tough. You have to be protective.

CC: Did you know the political career was over?

GC: You and I grew up in a time where if you got a really bad news article, you were going to see it again in a campaign a thousand times. (laughs) I had maybe a hundred thousand articles written about me.

The tabloids were ruthless, but many writers and many papers took liberties, a free rein to mix conjecture with rumor and speculation. Much of it was absurd, one periodical saying Carolyn was in town and killed Chandra. It reached bizarre when it was written that Carolyn had no thumbs. It was brutal when a fiction stolen from Clinton lore was published that Condit had fathered a child with an underage black girl. Condit, who has never hidden his affection for riding motorcycles, was painted as a sinister closet biker when a photograph of him at an office party, trying on a pair of chaps that had just been given to him as a gift, was sold to the tabloids. There were other stories of Chandra being dropped in the ocean as a favor to Condit.

Mike Mattoch, a scrappy Capitol lawyer now working as the West Coast counsel for a major insurance company, followed the Condit story closely. He met Condit in the garage of the Capitol basement when Condit was visiting Chuck Calderon. Condit was memorable, fashionably dressed, attentive even though Mattoch was just getting started in business. Over the years Mattoch says he recognized in Condit the steel you see in very few politicians. “You don’t get to the level of power Condit was reaching-the place where you tell people to shape up or you’ll walk away and bring others with you, without having the dexterity and nimbleness to understand all that can happen on a grand scale.”

The Condit Mattoch admired was not translating in the around-the-clock coverage on television. The onslaught was unyielding, and Condit was refusing to engage them.

CC: Were you surprised that so many lies were told?

GC: They had to lie. You have to remember I had the highest level of security clearance. Whatever character flaws I had in my life would have been found when they did the background check for the Intelligence Committee.

CC: Didn’t the police ultimately say you were not a suspect?

GC: They had said that, yeah, several times, but it doesn’t matter. It was free shot. You get a writer saying things like, “Well, I think Gary Condit knows more than he’s saying.” Or, “Gary Condit knows the guys who did it.” There’s no way you could ever...I’m sitting there watching this, and it’s just a lie, and at this point, the reporter knows it’s a lie.

CC: Is there a point where you are so deluged by this stuff that you become immune to it?

GC: It’s like somebody takes a knife and pierces your heart, you know.

CC: What do you think happened to Chandra Levy?

GC: I don’t know. It could be she went to the museum and this happened. We’ve learned since then that something happened to two other girls in the same park. It seems to me you should look at the guys that did the other two cases.

DENNIS CARDOZA

Dennis Cardoza got his first job in the State Capitol working for Gary Condit. He ran against Tom Berryhill for the State Assembly and won by less than one hundred votes. Berryhill, who works well with Cardoza now, says he was kicking Dennis’ ass until Gary Condit got involved and not only endorsed Cardoza but did commercials defending him.

Cardoza, a heavy-set, affable man, says he was approached to run for Gary’s congressional seat because the Levy scandal made Condit unelectable.

CC: Dennis Cardoza was asked on national television, and this isn’t verbatim but this is close - “Do you think Gary Condit had anything to do with the disappearance of Chandra Levy?”

GC: Yeah.

CC: Dennis Cardoza’s response is something like, “You never know what’s going on in the mind of a man.”

GC: It was something similar to that...the worst thing that can happen to you is that you really find out who your friends are. You’ve got people you think will walk through fire with you, as the flames come up, they’ll come running and give you a drink to get you through. Certainly he made the decision he was going to run for my seat, and that’s his right. I believe in that. That’s politics. He could have never beaten me for Congress had I not been called a murderer. I think he was pushed to do some of the things that he did, but he was open to doing it.

CC: Have you spoken to Dennis?

GC: No...look, I hope the district is happy with their choice and it works for them. I wouldn’t ignore Dennis. I wouldn’t look him up either.

CC: Pelosi was great, wasn’t she?

GC: Pelosi is great.

CC: Her quote was very clear. Nancy Pelosi said, “I don’t know what happened, but I can tell you right now, Gary Condit had nothing to do with it.”

GC: Yeah...look, I released everybody from having to endorse me. I know politics. When you’re in the barrel, man, you’re in the barrel. You’re the fish and they’re shooting you. There was no need for anybody else to get damaged. I will say it was heartwarming when Steve Peace (former member of the Gang of Five) paid for a campaign mailer to drop in my district. He didn’t tell me he was going to do it, and the gesture meant a lot.

CC: How was Carolyn through all of this?

GC: She did everything she could to be supportive and helpful.

CC: Did she chastise you at all?

GC: No.

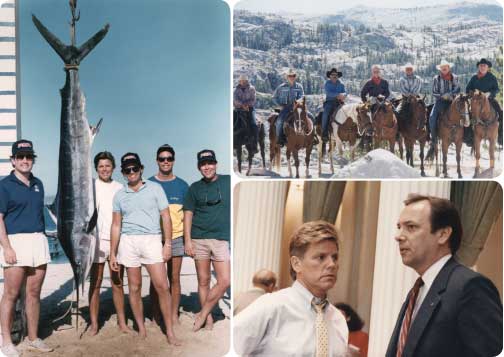

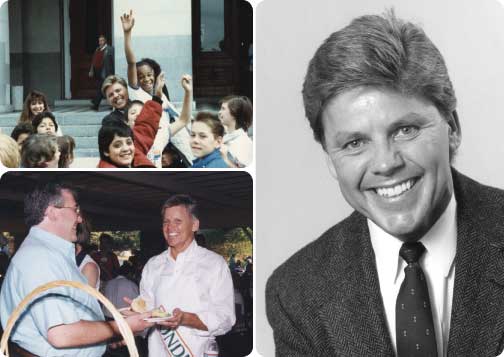

The Condit FamilyTHE CONDIT FAMILY

Carolyn is not silly or lost. She didn’t hide from the story. She tells about the press staking out ground in front of their home around the clock. Their garbage became a target, a ruthlessness that led to another empty story when Gary threw out trash miles from his Washington condominium. The letters she received during this period were ugly, and almost all of them from people she’d never met saying she needed to leave Gary.

“They don’t understand how long I’ve known him,” she says. “He’s a good man. I admire him that for all of the terrible things being said he was able to get up every morning and go outside.”

Gary’s parents, Adrian and Jean never lost faith in their son. The aging preacher spoke at the first rally when Gary announced he would seek re-election. They were a loving constant for the entire family, always at the house and holding their tongues when the press surrounded them, as proud of Gary when he was under duress as they were when he received credit for writing public policy.

Chad Condit was unquestionably qualified for the Assembly. He was the chief in Cardoza’s office and the central valley representative for Gray Davis. Not unlike Gary, he is precise when he is working on policy issues. He walked away from politics. Cadee is remembered for her toughness, even refusing entrance for a meeting to an uninvited constitutional officer. They both endured the indignity of being unfair targets when they were later charged with misusing Gary’s campaign funds and sued for two million dollars. When they declared their innocence and refused to negotiate a settlement the charges were dropped. A minor dispute with an ice cream franchise over two parlors made national news. Chad and Cadee quit the Governor’s office after the Governor criticized the Connie Chung interview, saying Condit was not forthcoming.

GC: (laughs) Gray’s given a lot of bad interviews in his time...hey, you don’t have to help me, just don’t do me any harm. I had people from all over the country call me and say, Gary, I’m going to tell you, if anything ever happens to me, I hope my kids act like yours.

CC: Do you miss Congress?

GC: I miss that backroom stuff you were talking about. I got very good at it. I think I ultimately would have been good for California as a deliverer of product and goods.

Gary Condit sees the United States from the ground these days. He goes for long trips and travels the back roads for weeks at a time. He does well in business. His grandchildren, a new one on the way, are a source of joy. His marriage is strong, a relationship that has lasted almost 45 years, and his children are a part of his everyday life.

If he has regrets, they’re not guideposts.

GARY (PHOTO COURTESY OF CHANNCE); GARY AND CAROLYN