Written by Aaron Read

Published Issue: Summer 2007

The Legislative Analyst

There is an article from the Journal of Economic History, September 1996, that tells the story of the California state budget battle of 1933.

In an attempt to close a 66 million dollar deficit without raising taxes, Governor James Rolph, the 27th governor of California, made decisions that sound all too familiar. He reduced the operating budget by $23 million, went after the highway budget, and allowed money from a permanent education fund to be earmarked for other purposes.

The front man for Rolph was the Director of Finance, Rolland A Vandegrift. Rolland gruffly told everyone there was no period after the initial A since it didn’t actually stand for a middle name. There wasn’t much nonsense to Vandegrift. He rationalized the reduction of per pupil spending from thirty dollars to twenty-four dollars by saying it was mathematically consistent with the Depression Era drop in the general price level.

Vandegrift was a gutsy, thickly built, balding forty-year-old from Washington D. C. who settled on a ranch outside of Sacramento. Nine years later, when the Legislature was dealing with a California emerging from the Depression and entering the Second World War, Vandegrift was the first person chosen to serve in the new role of California’s Legislative Analyst.

The Legislative Analyst and the supporting office of hard working policy wonks, number crunchers, pragmatists and clever soothsayers were created to provide the Legislature with an unbiased view of the fiscal implications of legislation and the Governor’s Budget.

Vandergrift kept the job even as he began dying seven years later from cancer and was unable to leave his beloved ranch. His loyal friend and closest aide, A. Alan Post, served as his conduit, acting director, and in July of 1950, his successor.

August Alan Post was named after a favorite uncle who was too successful in business to accept a cabinet job from the doomed President William McKinley. Post, natty, erudite, and remembered by contemporary legislators as part banker and part judge, joked somewhat insincerely that his first name was actually Anonymous. He was called Alan by his friends, and Mr. Post by everyone else, and for twenty-seven years he was the bump in the road when legislative and gubernatorial ideas needed to be converted into cost.

By his own description, Post ran the Legislative Analyst’s Office like a czar. Every letter sent from his staff of more than one hundred crossed his desk before a stamp was licked and pressed in the corner of an envelope. Every report was subject to his editing.

His logic was simple. “I never knew what the governor’s office, the legislators or reporters were going to be asking so I needed to know everything.”

Now, just shy of his ninety-third birthday, Post told California Conversations that the most important part of being the Legislative Analyst was “to be absolutely impartial.”

Post rarely went to lunch with anyone except his own staff. He didn’t want to be seduced by the politicians, many of whom he admired for their own disciplined approach to legislation.

“I was loved some days and hated others by the exact same elected officials. I didn’t always have a thick skin. I just never forgot that the responsibility of the Legislative Analyst is to get beyond the emotion of an issue to the cost.”

While running for governor in 1966, the political neophyte, Ronald Reagan, whenever he was confused on the details of a particular issue, told reporters the first person he would ask for advice would be Alan Post.

Reagan became the third governor to offer Post the Director of Finance position in his administration.

Post was not interested.

The relationship between the two was later strained when Reagan proposed a budget that contained an across-the-board ten percent cut of every item in every category.

Post lambasted the proposal as unworkable. “It didn’t make sense at almost any level,” Post said. “Much of our budget funding is statutory; some is constitutional, and many of the other cuts just didn’t make sense.”

In a hearing before the Assembly Chair of Ways and Means, Willie L. Brown, the up and coming legislator from San Francisco, Post explained, “If you adopt an arbitrary ten percent cut the end result is that the budget will be called the Property Tax Increase Act. Whatever the state fails to fund will be backfilled by the county that can only accomplish it by raising property taxes.”

A furious Ronald Reagan responded with the biting remark that, “Alan Post is more ambitious than smart.” Reagan then took it a step further by alleging the Legislative Analyst’s Office was “run over with Democrats.”

Post, a Republican himself, although not for much longer since he soon registered as a Decline to State, did something he’d never done before. He checked the registration of his employees and discovered “they were almost uniformly Republican.”

Post did not back down. Reagan did. In retrospect, Post said it was Reagan’s staff that probably caused most of the problems since Reagan tended not to get involved.

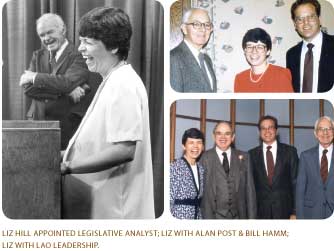

At the age of sixty-five, more interested in pursuing what would become a credible career as a painter, and amidst persuasive efforts from members of both parties that he change his mind, Post retired. He was replaced by an Ivy League graduate with a doctorate from Michigan and a long list of honors. His name was Bill Hamm. He proved himself a knowledgeable foil to a quirky Jerry Brown and his chief of staff, Gray Davis. He was also Alan’s nephew, the son of his wife’s sister.

“Honestly,” Post still says. “I don’t think it hurt that Bill was related to me, but there was a search committee and I didn’t influence them. I think they were surprised by the family connection.”

Hamm would keep the job for nine years before going on to what Post calls “more remunerative opportunities.”

The search for Hamm’s replacement was intensive.

The choice was a pregnant thirty-six-year-old Stanford and Cal graduate from inside the Legislative Analyst’s own team.

Her name was Elizabeth Hill.

Elizabeth Hill

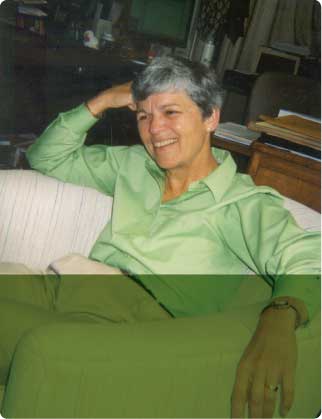

California Conversations spent time with Liz in her crowded office. There is more furniture in the small room than someone who designs such things would plan, and all of it appears a bit old, although it seems practical enough to be acceptable to Liz.

There are pictures on the walls of the three men who preceded her to a job that journalists have described as the conscience of the California budget process. There are other rectangular class pictures of legislators, and members of the Legislative Analyst’s Office gathering on the west steps of the Capitol.

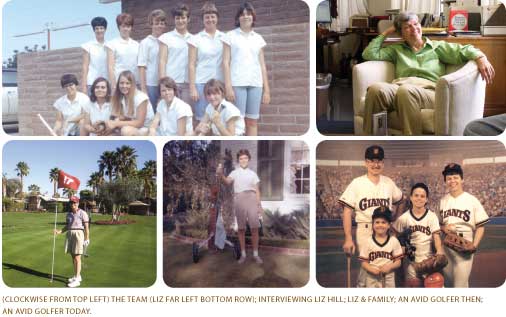

The same ease with which Liz conducts her standing room only press conferences following the introduction of the Governor’s budget is evident in private. The camera doesn’t change her. She admits to living a “rule-driven life.” That too is evident. Liz is more neat than stylish. Her clothes are coordinated and she wears them well on a slim frame, the pressed slacks and blouse chosen for comfort and looking practical rather than pretentious. Her hair is short, the way she has worn it most of her life, beginning to take on more gray than brown, and is combed away from her appealing, favorite sister face.

Her charm is in the fact that she is smarter than everyone else but smiles about it and let’s you keep up. She has flawless skin, very clear eyes, a sense of self that makes every place her world, and she looks much younger than her resume would suggest.

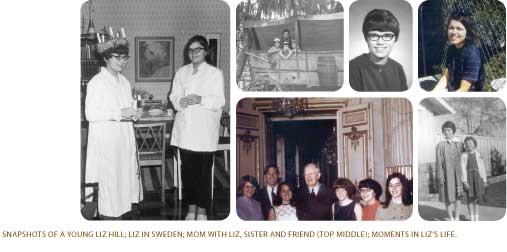

Elizabeth Hill grew up in the Central Valley town of Modesto at a time when open fields backed new neighborhoods and farmers supplemented their income flying crop dusters over the many vineyards. Her mom was a schoolteacher and her dad was a salesman; she taught elementary grade children and her father made a living selling mostly salt and spices.

It is no surprise that she was Student Body President and qualified for the California State Finals in speech and debate.

|

California Conversations: What was a rebellious moment?

EH: Well, I think the difficulty on the rebellious part is that my parents divorced when I was about 16. There wasn’t a lot of time to be too rambunctious in my teenage years.

CC: Was the divorce a traumatic event in your life?

EH: Oh, I’d say...you know...you try to learn from it. It certainly affected my relationship with my husband. He is also from parents who divorced, so we’ve worked on our communication over the years to be sure we are on the same wavelength.

CC: Were you in organized sports?

EH: There were no organized women’s sports in school until I went to Stanford. Of course it was before Title IX and our basketball team had the jackets of the swim team. (laughs) I’ve been to the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame in Tennessee, and it meant a lot to me because the first women’s intercollegiate basketball game was between Cal and Stanford. The score was 2-1, and Stanford won.

CC: Would life have been different if you’d been born a boy?

EH: Sure, but I feel like I benefited from many women who were pioneers in their fields. I do think if I’d been born later I would have liked to play more competitive sports.

Liz graduated at the top of her class from Downey High School and was accepted to Stanford University. She received what was called a state scholarship, based in part on academic record and financial need. Those scholarships have evolved into Cal-Grants. She delayed her first year and accepted placement as an American Field Service student in Sweden.

CC: How long did you stay in Sweden?

EH: I lived for a year one hundred miles from the Arctic Circle. It completely changed my life. I’d never even seen snow fall out of the sky. When you’re outside of your own environment you ask yourself a lot of questions, you wonder what is really important, and you take in the diversity of cultures and opinions. (laughs) I learned to speak Swedish but not before I asked my Swedish mother if she was a sewing machine. We still laugh about that, even today.

CC: Is your life populated with old-time friends?

EH: I’d say I’m a person who has a few good friends.

CC: You were at Stanford during Vietnam?

EH: Yes.

CC: Were you a student protestor?

EH: There were certain days when people were asked to boycott everything. But, I had a job in the food service, and I really didn’t feel I could boycott my job. That was part of a way I could stay in school.

CC: Were you shaped politically at Stanford?

EH: That’s a good question. In Sweden there wasn’t poverty, and that really affected me. And there were kids at Stanford whose food budget for the week was more than my family would spend in a month. There were different sorts of values to consider which did shape my views.

CC: Did you buy into the hippie culture?

EH: Not much. I wasn’t too much of a hippie.

CC: Did you inhale?

EH: (laughs) No.

CC: Did the politicians of that time inspire you?

EH: I was 12 years old when John Kennedy was elected. I remember the 50-mile walks and the long swims that were a part of the President’s Physical Fitness Challenge. There was an energy that I thought was really exciting.

CC: Were you Catholic?

EH: No, Protestant.

CC: Are you still?

EH: I think my Swedish experience affected me, because there were a lot of solid people who weren’t practicing formal religion, but at the same time had strong values and goodness in their lives.

CC: You don’t attend any church?

EH: No.

CC: You didn’t bring your son and daughter up in any church?

EH: No. My husband and I felt it was important for them to figure out their own religious beliefs. (Liz has two grown children; a married son and a daughter away at college.)

CC: Did you have interesting jobs?

EH: I worked summers in a cannery. Then I got a job working at CalTrans. I was hoping to work full-time at CalTrans, but when I finished college they were laying-off thousands of folks. Actually, my mentor at CalTrans said I should think about a position in the Legislative Analyst’s Office.

Liz takes a job as a staff analyst within the office of the Legislative Analyst when she is only twenty-six years old. The California budget is broken into issue areas and she is assigned criminal justice. On a staff of more than one hundred, only a few are women.

CC: Criminal justice a main issue area of concern for you?

EH: I didn’t really know anything about criminal justice but that was the assignment that was open. It was interesting dealing with the departments, lots of good public servants, as well as dealing with the advocacy community. I felt like a sponge. I did that assignment for a few years, and then I became the head of the Welfare and Employment Section, as we called it at the time. My son was born when I was in that assignment.

CC: Were you fast-tracking? Are people saying Liz is going places?

EH: It was a great opportunity early in my career. It wasn’t clear to me then that I would have any sort of shot at the head job.

CC: Are you an accountant at this point or are you a policy wonk?

EH: I’d say a policy wonk type. I think budgeting is a people business.

CC: Did being a woman mean you needed to behave differently?

EH: The atmosphere was collegial, but you had to pay your dues. The legislative committees and the departments didn’t always know what to do with a woman in the group. I remember my first meeting with the Department of Justice, which was about twenty special agents and me. The agents settled into the meeting and crossed their legs. I saw a number of guns waiting to be drawn if the need arose. I was intimidated. I have to admit it. I just kind of decided, hey, I like the work and I was going to do the best that I could and see what happened.

In 1986, with broad legislative support, Liz was chosen as the Legislative Analyst.

CC: ...a controversial decision?

EH: There were a number of candidates inside the office, and we all interviewed with the committee. But, you know, I think there was also some interest among our colleagues that the job go to someone from inside the office, who knew how the Legislative Analyst functioned.

CC: That’s your answer?

EH: (laughs) Yes.

CC: Alan. Were you close to him?

EH: I only worked one year under Alan. He was a legend at the time. I worked nine years under Bill Hamm. I thought he certainly built on Alan’s traditions in the office. He got us into the computer age; started recruiting more at college campuses and the like. I very much enjoyed our association.

CC: Do you go to them for counsel?

EH: I have a number of times over the years.

CC: Who else do you go to for counsel?

EH: That’s a good question; certainly members of the Legislature and my family. And I always turn to people in my office.

CC: Do you hire your staff?

EH: Yes. They officially become legislative employees.

CC: What would be the reason for firing someone?

EH: We’re not a civil service organization and for some people it’s just not a fit to do the type of analytical, non-partisan work in the time frame that we have to meet the Legislature’s needs.

In 1990, the people of California passed Proposition 140, which not only created term limits but significantly reduced the overall budget of the Legislature. The Legislative Analyst is supported evenly by the Senate and the Assembly.

CC: Prop 140 decimates LAO, doesn’t it?

EH: We had a tough time because our office budget was cut 60% and most of our budget is staff related.

CC: Wasn’t there discussion of making LAO independent of the Legislature?

EH: Yes, Proposition 158 went on the ballot in 1992 proposing to move our shop out of the Legislature’s budget and there was a companion piece for the Auditor. Neither of those measures passed. The Auditor’s Office was closed for a period of time as a result of Prop. 140.

CC: You had the wrong fundraisers.

EH: All we could do was make a sound argument for an independent voice.

CC: Are you building the staff back up?

EH: Actually, we had 106 staff at the time of 140’s passage. We’ve come up from 46 staff after the cut to 55 now. Today we’re at the office’s staffing levels of the early 1970s. In addition to our budget work, we used to do about 3,500 bill analyses a year and we had a representative testifying in the two Appropriations Committees. We had to figure out how we could do the job with 60% less people. So, we got out of the ongoing bill analysis business; kept the budget the focus of the office and broadened everyone’s assignment.

CC: Does policy dictate budgeting, or does budgeting dictate policy?

EH: I usually think the programs drive the money. But it gets tougher when you continue to address out-of-balance budgets. Then I think the answer to your question gets murkier, because when you’re not keeping up with costs, you begin to ask is the program still working the way the Legislature intended.

CC: Twenty-one years gives you a view of different leaders and different problems.

EH: We have gone through a number of economic cycles in my time in the office.

CC: Governor Wilson accused you of advocacy.

EH: I remember his comment being related to welfare reform and I don’t feel that was advocacy at all. We helped the Legislature view welfare reform from a long-term fiscal perspective based on elements successfully evaluated in other states or tried earlier in California.

CC: Is advocacy a dirty word for the LAO?

EH: We have to be sensitive that our advice is analytical.

CC: Do you feel the information you’ve provided tends to lead the Legislature in a certain direction?

EH: We are charged with looking for economies and efficiencies. I think we are instrumental in terms of helping assess the overall fiscal condition of California. We do it not only for the year we’re in, but the years coming down the road.

CC: It seems that when you issue your budget analysis, there’s invariably a headline - “Analyst Rips Governor’s Proposed Budget.”

EH: The Legislature often has different priorities than a governor. Part of our job is to help our bosses figure out where those differences are and how to make their priorities work.

CC: The first governor for whom you worked was Deukmejian.

EH: As part of the Legislature, we tend to interact with governors and their staff during the budget process. Jerry Brown was in office when I first joined the LAO.

CC: Did you have any personal interaction with Jerry Brown?

EH: Governor Brown called Mr. Post when he had a concern about an analysis I had done of the Arts Council.

CC: Have you had personal interaction with each governor?

EH: I have met them and, of course, a number of them served in the Legislature where I had the opportunity to interact with them.

CC: Do you have a favorite?

EH: That’s a slippery slope so I won’t go there. I do have admiration for a politician’s ability to take information, whether it’s on the budget or policy, and figure out a course of action that can be adopted. Governors and legislators deal with such a wide range of complex issues.

CC: Willie Brown tried to put you out of business in 1993.

EH: The office was zeroed out of the proposed Assembly budget for a period of time but ultimately funded by both houses that year.

CC: Can you be fired?

EH: Yes, any day, by the Joint Legislative Budget Committee.

CC: Do you ever worry?

EH: It’s interesting you ask that because when I was in graduate school we learned to always keep our bags packed. I thought that was sage advice, because if you are going to work in the policy arena, you have to be sure you’re in the position to say no. My husband and I structured our home finances to make sure we were each in that position if the situation called for it.

CC: Prop 98 sets a percentage of the budget that must be spent on education - complex and necessary or convoluted and confusing…

EH: Well, I’m not sure it’s delivered what the education community hoped for. I think often it has become the ceiling rather than the floor and it has shifted debate from what California really needs to fund in education to how do we meet the guarantee. And because Prop 98 is tied to the economy, if you actually look at how Prop 98 funding has gone since 1988, it’s been on a roller coaster. We recommended in the early ‘90s that the state unlock the budget so decision makers can set priorities rather than have the budget driven by so many formulas.

CC: Will it happen?

EH: Well, stranger things have happened. I didn’t think the Berlin Wall would come down. I didn’t think the Soviet Union would break up. So, I think if you’re a budgeteer you tend to be the type of person who sees the glass half full rather than half empty.

CC: Do term-limited legislators rely on you more than their non-term-limited counterparts?

EH: Clearly, we have the institutional knowledge, which can be helpful to new members. We help members understand why a proposal didn’t work the last time, maybe some of the upside or downside risks. I think the institutional role is important, particularly on issues like infrastructure or long-term financing.

CC: Your analysis comes out a week after the Governor’s budget?

EH: We put initial comments out about a week after and then the detailed analysis is usually released the third week in February.

CC: Is that a scary day for you?

EH: Yeah, I’d say it is.

CC: It’s a very bare stage. Are you ever thrown for a loop?

EH: Oh, of course. Luckily, my senior colleagues are in the room to help me when I get totally stumped. I struggle myself to be sure I’m translating the issues in a not too techie way so that it is more understandable.

CC: Have you ever made a major faux pas?

EH: Yes. The nature of forecasting is you know you’re going to be wrong sometimes. We’ll change our recommendation if we’re convinced we made a mistake or there was some piece of information we didn’t consider, or maybe didn’t understand appropriately.

CC: Is the Governor’s Department of Finance your rival group?

EH: When our office was cut by 60%, it was actually our colleagues in the Department of Finance that threw us a big picnic in Capitol Park. It is a professional relationship between the two offices. We have different bosses. We both want to get our numbers right, and we can have an honest disagreement about the numbers. I have lots of respect for them.

CC: Has it ever gotten ugly between LAO and Finance?

EH: I think sometimes there have been some difficulties over information.

CC: Has anybody ever tried to influence your report?

EH: Oh, sure. We know folks will try to influence our report, and it is important for us to get as much information as possible, whether it’s on the budget or our ballot work. We get the proponents and opponents of initiative measures in the room together to help us understand their respective points of view.

CC: That’s the discussion that should be taped and the public should see.

EH: Those can get heated and, of course, in a lot of the propositions there is a great deal at stake.

CC: Have you been forced to make changes?

EH: The courts have required a few. We are supposed to write for the average reader in California. One year we had a measure that affected the court, and we chose not to use the word “plaintiff” because we thought it was too techie of a word for the average reader. But the judge felt that “plaintiff” needed to be in the analysis and ordered the change.

CC: Do your moments of fallibility haunt you?

EH: Oh, you don’t like making mistakes, but you’re on to the next issue.

CC: So, what’s the expletive when it goes wrong?

EH: (laughs) I don’t know if I want to share that with your readers.

CC: Do you swear?

EH: Oh, sometimes, sure.

CC: Do you raise your voice?

EH: Yes.

CC: Do you yell at staff?

EH: I don’t like to be yelled at myself, and I try not to do that either. I mean this job takes a whole lot of each person doing their part or we don’t get things out the door. It takes us all rowing the boat at the same time.

CC: How much of the actual writing of the LAO reports do you do?

EH: I review our documents to make sure I understand the topic, that we have clarity, that we make an analytical case. But in terms of the overall writing, it is done mostly by my colleagues.

CC: What kind of hours do you work?

EH: I think this last January and February I worked about 200 hours of overtime. And then again May and June are the other big periods as the Legislature is putting a budget together.

CC: Must put pressure on the home life?

EH: I generally try to protect the evenings and the weekends as family time. I always tried to not take the work home, at least not while the children were awake. There’s no doubt the cycle made it hard on my family sometimes.

CC: Only four people have held your position. Is this an extraordinarily difficult job?

EH: It is very challenging because California, just over my time in the office, has changed dramatically and yet a lot of our governmental systems are the same ones that have been in place for many decades. It troubles me to see these constant budget problems.

CC: What budgeting trends frighten you?

EH: What concerns me is the focus on locking up the budget process for certain groups rather than thinking of the interest of the state as a whole.

CC: Can we afford to keep up?

EH: I think that your question goes to a fundamental question of whether or not we have a disconnect between our revenue system and our spending structure, and what the state’s priorities are overall.

CC: Do you think the California of our children can be better than what we had as children?

EH: It will be very different. I think it’s hard to assess “better,” but I look at how many more people are going to the university today than even when you and I went. There’s a lot of positive beneath the difficulties that we’re facing. We are working to solve problems.

CC: You feel positive?

EH: I feel hopeful.

CC: Of course you do.

EH: (laughs) I do.