Written by California Conversations

Published Issue: Summer 2011

Shirley Marie Burns was born into a military family, became a nurse and a soldier herself, married an army man, spent most of her life travelling from assignment to assignment until after ten months of asking for the opportunity, personnel sent her in the middle of the 1960s to a distant post in Vietnam.

In her own words:

My orders got me to San Francisco, and then I had to fly ‘standby’ to Vietnam.

My tour was tiring and sad, yet the most rewarding time of my life. I arrived at Tan Son Nhut Airport in Saigon. I was dressed in winter greens and high heeled shoes.

The nurses were taken to the Post Exchange and told to buy all the feminine things we would need for one year.

After lunch at the Officers’ Club we put on helmets and flack jackets and boarded a bus for Cu Chi. We were escorted by several armored vehicles with helicopters overhead.

I worked with a group of other nurses at Cu Chi to set up the 12th Evacuation Hospital, a M.A.S.H. unit basically, although that term was not used at the headquarters for the 25th Infantry Division.

It was muddy everywhere and wet. It seemed to just suck you down into it. Our new living quarters, our hooches, had wood sides and a tent top. The guys could not wait to show us our new restroom, our outhouse. They had built them and put pink toilet seats over the holes. They were thrilled and most of us started crying.

I was promoted to 1st Lieutenant.

Working in the rain and mud, it took nearly a month to open for business. Then the business came...and kept on coming. My life was never the same.

The next few months were a series of highs and lows.

The kids...bloody, dirty, hurting, wanting the nurses to hurry so they could get back to their unit, to their buddies.

The MedEvac helicopters were nearby at all times, day and night. We had twelve-hour shifts...when we had shifts at all.

There were trips to the surrounding villages to dispense medicine. When the pills we gave away started showing up with captured Viet Cong, we gave only injectable meds.

The mortar attacks were a part of working at Cu Chi. There was a direct hit on my ward and it killed two GIs instantly. That seemed so unfair.

The highs were less numerous, but the contrast seemed so remarkable. R&R in Penang and Tokyo, the mai tai party when the new general took over the 25th Division, the guys coming over from base camp with steaks just to say, ‘thank you.’

Shirley served as the first female commander of the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) in the State of California. She also chaired the California VetFund Foundation.

By the middle of 1967 the Vietnam War was ramping up and the stories of the bloodiest battles were being shown on American television. The TET Offensive, the cruelest battle of the war, was less than a year away, and Walter Cronkite, the venerable television newscaster, was about to say that our goals in Vietnam were untenable.

Ray Snodgrass was a recent high school graduate working the fire season for CAL FIRE when he got the notice to report for his army physical. His mother cried at the prospect of Ray going to war and her tears were not lessened when the doctors told him he was 1A and physically fit to serve in Southeast Asia.

A month later Ray was told to be at the induction center for his swearing-in. He got his release from CAL FIRE with the promise that he could work for them again as soon as his time in the service was complete.

On the morning of his arrival at the induction center, Ray was outside in a long line of new enlistees.

Before they could all make it into the building there was a ruckus. Several long-haired, colorfully dressed young people began making noise and forcing their way into the induction center ahead of the draftees. It is almost quaint to admit it now, but there really was a time when hippies existed as part of a peace movement that was sweeping the country. There was a skirmish; it almost got violent before the hippies ran down the street screaming that the war needed to end. They had stolen papers from the counter and were waving them in the air.

Ray eventually got invited inside. He was told to stand in place while names of the new draftees were called out and they were sent through a second door to be sworn in. There were a half-dozen young men left in the lobby when the soldier in charge asked each of them their name. Ray was one of them.

“The hippies stole your files,” the soldier told them. “We can’t take you into the army today. You need to come back and have another physical and begin the entire process all over again.”

“How long will something like that take?” Ray asked.

“We’ll call you.”

It was another month. Ray went back to the induction center as he was told, and a new doctor did the physical. This time the doctor noticed that Ray’s small toe on his left foot was bent and crossed over the toe next to it.

“Is your toe always like this?” the doctor asked.

“Yes.”

“Do you remember when this first happened?” the doctor asked.

“Yes, I broke my toe jumping off the back of a pickup truck when I was six years old.”

“It is a deformity,” the doctor told him.

“I don’t even notice it.”

“It will be impossible for you to live an entire year in combat boots,” the doctor opined.

“I wear boots on my job,” Ray answered.

“Combat boots are for marching,” the doctor snapped.

Ray was declared ineligible to serve in the military. He was sent home without an option to appeal.

The hippies who had awakened that day with the intent of interrupting the military had managed to change Ray’s life.

All of the draftees who Ray was supposed to join on that first trip to the deployment center were immeasurably altered by going to war. Many of them died. All of them were different because of the experience.

Ray went back to work the following week. He would have a remarkable career in the fire service. He would twice be selected Firefighter of the Year, and two decades after his dismissal from the induction center he was elected by his peers to be president of CDF Firefighters.

Years before he decided on a life in public service, Juan Vargas had a higher calling. The Senator was a Jesuit seminarian, a young man who actually spent time living in a cell vacated years before by another Jesuit seminarian, Jerry Brown.

Juan has always held a special interest in South America. Part of his mission was spent in that war-torn continent bringing a message of service and peace. On his return, he joined a group of other Jesuits on a trip to the Pentagon to protest American intervention in El Salvador. It did not go well. There was a confrontation as they marched. Juan was arrested.

It is a long road to the priesthood. There are many chances to change one’s mind.

Juan kept his faith, but eventually left the Jesuits. He went back to school and was accepted to Harvard Law School.

While at Harvard, he played basketball and became friends with another student named Barack Obama.

The story, of course, is that Obama managed to get himself elected President of the United States.

A third friend of theirs from Harvard wanted an appointment from Obama. The President offered him Undersecretary of the Navy.

Juan was invited to the Pentagon for the swearing-in ceremony of the Undersecretary. He arrived and amidst heavy security got into line. He noticed a young woman, a second lieutenant, near the front of the line holding up a sign that said “Juan Vargas.” He got out of line and introduced himself to her.

She told him to follow her and they bypassed the other soldiers standing guard near the machines where everyone else needed to pass.

“Have you ever been to the Pentagon?” the young second lieutenant asked Juan.

“I have,” Vargas answered. “I’ve just never been inside.”

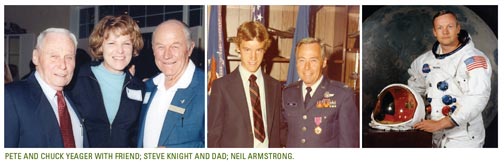

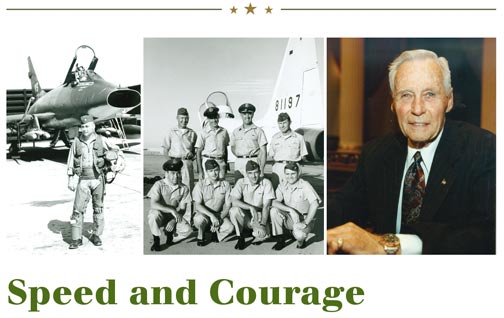

Assemblymember Steve Knight was born at Edwards Air Force Base, a former water stop for the Southern Pacific Railroad, on the borders of Kern and Los Angeles counties. The base itself was named after a test pilot who perished along with five others in a tragic mission that tried unsuccessfully to stretch the limits of aviation technology.

It makes sense that Steve breathed his first breath on a military base. His father, a state assemblymember and senator in his twilight years, was the legendary test pilot Pete Knight.

It is impossible to put the challenges Pete Knight faced into perspective. At a time when test pilots were dying at a rate of one per week, Pete Knight was in the middle of a brilliant thirty-year Air Force career that would see him test experimental aircrafts that no one had ever flown before. He would also fly in excess of 250 combat missions in Vietnam.

No one has ever flown an airplane faster than Pete Knight. Ever.

Forty-four years ago Major Knight flew an X 15 A-2 at more than 4,500 miles per hour or just shy of seven times the speed of sound.

He took the aircraft 281,000 feet into the air and earned the extraordinary distinction of becoming an astronaut for flying an airplane in space.

“My dad rarely talked about his accomplishments,” Steve says. “I remember one time being on a commercial flight with Dad when a passenger started talking about various experimental airplanes.

Even I could tell it was all bluster and he had no idea what he was talking about. My dad just sat there expressionless. He refused to straighten him out while I wanted to explain to the guy that he was in the wrong company to be pretending his expertise.”

The test pilot fraternity is unique. You can’t sit on a commercial flight and talk your way in. There is no honorary group. It is not possible to imagine the independence and courage it takes to climb alone into the cockpit of an airplane that no one is sure how it will behave, a plane that is designed to go higher and faster and move with greater singularity than any other type before it, and fly at great speeds and altitude to find out if it works.

The astronaut, Gordon Cooper, the final member of the Gemini team and the seventh American to fly solo in space, was asked once who he admired most. He answered something to the effect that the greatest men he ever met were those who had the courage to get into a hurtling piece of metal and make it fly according to specifications.

The first test pilot to break the sound barrier was lionized in the movie “The Right Stuff.” He was Chuck Yeager. He was a war hero who distinguished himself in Germany and Asia. A man noted by his colleagues for his abilities and his daring. General Yeager spent his long career flying combat missions and, later, test flights. He commanded squadrons and he flew solo, and with both daring and panache he was an ace who was admired greatly by his fellow pilots long before he became famous.

The first man to step on the moon flew experimental planes before he bounced on the lunar surface on July 20, 1969. A naval aviator and an engineer, Neil Armstrong was known for being self-effacing in spite of his many accomplishments. He was a combat veteran in the Korean conflict and, like Knight and Yeager, he was an old pro from the test pilot Mecca of Edwards Air Force Base. Armstrong would fly thousands of hours in complex aircrafts before he was chosen for his high-profile mission; and like all of his colleagues, find close friends among those who did whatever their country asked of them and did not always survive the task.

Steve Knight remembers a time when his dad attended a funeral service for a pilot friend. Steve was invited along. Afterward, Pete Knight invited Chuck Yeager and Neil Armstrong back to the house. The three great men sat in the kitchen for hours drinking beer and talking about old times. Steve sat in the kitchen with them.

“What did you say to them?” we asked Steve.

“Nothing, not a word,” the Assemblyman answered. “I just listened and it was one of the best days of my life.”